Infighting as the Oba of Benin tries to seize all rights to the bronzes

Dispute shows that the ‘moral’ case is not always clear cut

Passed as part of the Charities Act 2022, measures that have been suspended relating to deaccessioning in museums and the return of objects to source countries will now come into force.

The idea is to make it easier for institutions to return disputed objects on moral grounds. This is not as easy as it might seem, however, as different moral codes apply depending on who and where you are.

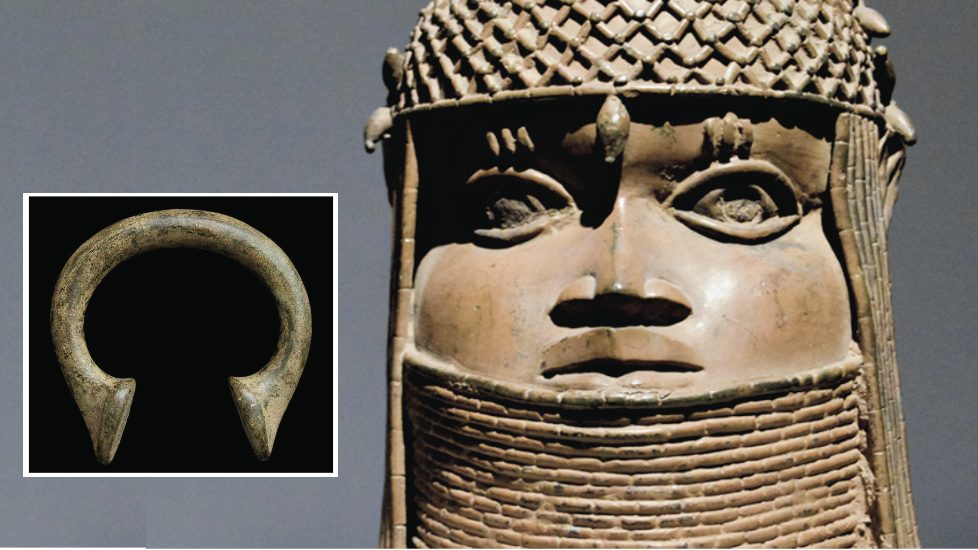

Evidence of this can be seen in the Horniman Museum’s return of Benin Bronzes to Nigeria in 2021, under earlier legislation. While the moral grounds for sending the bronzes back were their status as looted items from the British punitive expedition of 1897, the museum ignored the fact that they were the product of slavery – literally so as they were made from slave currency – which had enriched the Oba of Benin.

As the BBC revealed on November 13, however, the bronzes that have been returned have sparked widespread controversy. This is firstly because the Nigerian government has handed them over to the current Oba, thereby rewarding the direct descendant of one of Africa’s worst slavers. The descendants of former slaves in the US had protested through the courts against the return of bronzes from The Smithsonian, but lost their case because, as the bronzes had already been returned, the court decided it lacked jurisdiction in the matter.

The Oba’s links to the history of slaving have been entirely expunged from the record in Nigeria and are largely overlooked by the world’s media and those who have pressed for repatriation, but that does not mean they have been forgotten.

New museum remains shut as Oba launches legal case

Now the bronzes’ new home, the much-anticipated Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) due to open in Benin, the capital of the Edo region of Nigeria, remains shut. Its construction and fitting out has taken five years, and the idea is for it to provide jobs and boost the local economy. Funded to the tune of $25 million by British Museum fund-raising donations, among others, it has found itself at the centre of a political storm for various reasons, with permission for the land to be used to build the museum now revoked.

“Much of it comes down to internecine rivalries at a local state level, as it was Edo’s previous governor Godwin Obaseki – whose term in office ended last year – who was a major backer of the museum,” the BBC reports.

“And it seems the administration of the new governor, a close ally of the local traditional ruler, known as the Oba, may want more of a stake in the project. The protesters on Sunday, for example, were demanding that the museum be placed under the control of Oba Ewuare II.”

True enough, as it turns out, according to the Benin media, which reported on November 24 that the Oba is attempting to wrest control of the returned artefacts and any fund-raising operations linked to them by suing the museum promoters and demanding that neither the museum nor anyone else should be dealing in Benin artefacts without his permission.

“According to available court documents, the claimant is contending among others, that the Oba of Benin, being the sole custodian of the culture, tradition and heritage of the Benin Kingdom, is the only rightful person to determine where the returned looted artefacts and other items of Benin heritage should be kept,” The Benin Sun reports.

The Oba is calling for the court to declare him the sole owner, custodian and manager of repatriated looted Benin artefacts.

He is also demanding that no one else – neither individual nor institution – should be able to raise funds from outside Nigeria in his name, and he wants a perpetual injunction “restraining the defendants, their servants, privies or agents from establishing, opening and operating any museum in Benin City, Edo State, dealing with Benin artefacts without the consent of the Oba of Benin”.

One rule for the governor, another for the Oba, when it comes to family connections

In May 2023, Cambridge University’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology delayed the return of 100 of the bronzes when it feared that they would not be put on public display after outgoing President Muhammadu Buhari decreed that the Oba was the rightful owner of all returned Benin Bronzes and was responsible for the management of all places where the artefacts were kept.

One of the curious aspects to the internal political disputes over the issue in Nigeria has been the objection to former Edo state governor Obaseki, who was behind the establishment of MOWAA. The objection rests on the fact that he is the direct descendant of a palace official who was appointed as prime minster by the British after the 1897 punitive expedition. If such a direct link would disqualify him from involvement, why is the same standard not applied to the Oba himself following his forebears’ bloody past?

Clues come from reporting on the Restitution Study Group, which has led the campaign to retain the bronzes in public institutions within the United States: one argument is that while the manilla slave currency was indeed used to make the bronzes, some of it came from trading other goods, so it is impossible to say which was which. Another is the view shared by Nigerian art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu, a professor at Princeton University and an activist at the forefront of the campaign to return looted artwork. He dismissed the Restitution Study Group’s leader, Ms Farmer-Paellmann’s comments as sounding “like the arguments that white folks who don’t want to return the artefacts have made”. Whether this is true or not, he does not address the historic Obas’ role in sending more than 100,000 people into slavery down the years.

What will the governments and museums around the world, so keen to hand back the bronzes for public benefit, do now?

- Image top: A Benin bronze, and (inset), a manilla, probably made from a brass composite (Ashmolean Museum). The name comes from manilha, the Portuguese word for a bracelet.

Recent Comments