by ADA | Jan 21, 2026 | Views |

Lack of data, high costs, poor resources and risks to human rights continue to blight the mission to trace trafficked cultural property

Study on measures to increase traceability of cultural goods in the fight against cultural goods trafficking at the Member State level and at the EU level (Final report)

This report into what the European Commission believes should be done next to tackle the blight of cultural property trafficking is an eye-opener. It is telling that initial publication should take place just three months before the final enforcement of the previous mass enforcement measure, Reg 2019/880 on import licensing.

Nonetheless, this new report is fascinating because of what it reveals: specifically, the ongoing lack of data despite decades of study and multi-million euro funding for research; and high levels of self-awareness indicating an overwhelming lack of confidence in the viability of what is being proposed here. A continent-wide system linking up all existing databases (and adding new ones where needed) after they have adapted to a single standard could be a very effective means of combatting crime. However, as this 320-page report makes abundantly clear, too many obstacles persist to render this ambition anything but a fantasy.

Essentially the objective of the report is to pave the way for the introduction of a compulsory EU-wide registration and standardised due diligence system for reporting cultural property transactions. The idea is that this would allow national databases to interact with each other to create an EU-wide safety net and monitoring system.

EU-wide standardised network of databases

A continent-wide system linking up all existing databases (and adding new ones where needed) after they have adapted to a single standard could be a very effective means of combatting crime. However, as this 320-page paper makes abundantly clear, too many obstacles persist to render this ambition anything but a fantasy. Here are a few of the issues it raises:

– What would an effective single standard look like?

– Who would decide on what should be included?

– How do you define the parameters of what should be included on the databases?

– How do you get all Member States to comply when only nine of the 27 currently have databases and they are incompatible?

– What value threshold would you introduce if, as stated, the intention is to focus on high value goods (a wise course)? Matching the AML standard, as mooted, would mean €10,000, but that is very low and would risk overwhelming business, customs and possibly the databases themselves.

– Who would have access to the databases bearing in mind the historic protectionism exercised by existing databases? The report acknowledges that they would be ineffective if not publicly accessible.

– How do you persuade Member States to proceed when they have been unwilling so far and would largely have to fund the project themselves and set up support and enforcement teams? Initial estimated costs are €36.8 million, with an extra €383 million to link up Member States effectively.

– Why do we need further regulation when the same objectives are covered by existing measures such as EU Reg 2019/880 on import licensing?

– The report repeatedly emphasises the need for EU standards and human rights to be honoured, yet acknowledges just as repeatedly that what is being proposed risks breaching them.

As revealing is what comes in the preamble, where we discover the following:

– Data is hard to find and reliable data is largely non-existent, but art and antiques are seen as relatively high risk because they can be traded.

– Compliance value thresholds and claims of crime levels rely largely on guesswork.

– Law enforcement and others mostly extrapolate international crime levels from a few individual cases.

– Many of those cases involve art and criminals but not the art market.

– Risk categorisation for Terrorism Financing and Money Laundering are guesswork, with nation states acting on wish lists from law enforcement bodies and the belief that the risk must be high because it involves goods that can be traded.

Art Market input

As explained on page 277 of the report, apart from a few unspecified targeted interviews, consultation on this study with the art market was as follows:

An online survey targeting art market participants was launched in April 2024 and data was exported in July 2024. The survey aimed at gathering information about perceptions of the prevalence of trafficking, transaction recording practices and administrative costs and compliance costs incurred. A total of 32 replies were received from art dealers, galleries, auction houses, antique dealers and gallerists from Austria (1), Belgium (1), Czechia (1), Germany (11), France (2), Portugal (1), Sweden (6), Switzerland (1), the Netherlands (4) and the United Kingdom (3).

by ADA | Jan 5, 2026 | Views |

No questions asked; no curiosity – how the media deals with attacks on the art market

One of the most concerning aspects surrounding fake news as it applies to the subject of cultural heritage is the widespread failure of the media to address the issue properly.

While a daily stream of reports chide the international art market as a haven for criminals involved in theft, smuggling and money laundering, vanishingly few journalists ever seem to check the validity of claims being put out by governments, law enforcement, NGOs and others.

In 2022 and 2023, it appeared that we had turned a corner when European Commissioners and senior officials at UNESCO finally accepted that massively inflated claims regarding the value of illicit material being trafficked across the world were simply untrue.

One of the most important papers on the matter at the time was the Cambridge University Press published The illicit trade in antiquities is not the world’s third-largest illicit trade: a critical evaluation of a factoid. Its authors, Drs Neil Brodie and Donna Yates had long been critics of the trade, but had come to agree with the evidence-based arguments promoted by the industry that the claims were false and actually harmed the interests of heritage and culture because they risked encouraging further thefts.

Regulation that has the potential to harm legitimate trade has come into force on the back of false data promoted by those who wish to prevent that trade – the European Union’s new import licensing law 2019/880 is a case in point.

The false impression created by bilateral agreements

The rise of bilateral agreements, particularly between the United States and other countries (at least 35 now relating to cultural heritage) spreads a false impression that countries of origin are able to reclaim artefacts because US law enforcement is doing a great job of finding looted and trafficked pieces. The reality is that these agreements bypass the usual property rights cited under the US Constitution, as well as dispensing with the need for evidence, both of which would protect citizens under normal circumstances. Instead, they effectively wave through a kleptocratic system that allows the state to seize its people’s possessions and use them for soft-power purposes. Then the media, on a global basis, simply parrot the claims of the authorities rather than asking for evidence that the items in question were, indeed, illicit.

This is all bad enough, but the failure of the media to highlight the scandal, even when presented with the evidence, effectively makes it complicit. It’s almost as though reporters are simply reprinting the media releases from the Manhattan District Attorney’s office and the State Department. No questions asked; no curiosity.

The same unquestioning approach has made gospels out of official reports which simply do not stand up to scrutiny, such as the deeply flawed February 2023 Financial Action Task Force report into money laundering, trafficking and terrorism financing related to art, Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in the Art and Antiquities Market.

It would be easy to blame the lack of training and resources for the media’s failure to examine these issues more robustly or even carry out basic fact checking. However, as all this has gone on, many leading media outlets have indeed taken a robust approach, but only where articles support the market position and expose the untruths leveled at it.

Articles supporting the market are ‘lost’ on submission

Antiquities Forum knows of numerous instances where articles pitched with every fact supported by detailed footnotes and/or embedded links to primary sources have been ‘lost’ by the commissioning editor – sometimes two or three times – with renewed submissions ultimately ignored or refused without reason. These are articles from expert writers and journalists who have had no problem securing publication with those same titles on other subjects.

At the same time, stories that are patently untrue or unsupported by evidence are published without question – clearly without any fact checking going on.

Comments under articles have been equally ‘mislaid’, ignored or simply censored if they challenge market critics. It seems no one in the media is interested in the widespread abuse of citizens’ rights, including the reversal of the burden of proof – now commonplace – when it comes to ownership, so that your property is considered stolen unless you have the paperwork to prove that it is not. Surely the media should be interested in something as fundamental as the decision to treat people as guilty rather than innocent as a basic standard of civilised society. But apparently not.

As a former member of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) that briefs Congress, lawyer Peter Tompa is a noted authority on the law as it applies to cultural heritage. A prominent campaigner among the coin collecting community, senior official of the Global Heritage Alliance and author of the Cultural Property Observer blog, as well as numerous articles in Cultural Property News, he is exactly the sort of expert that the media should be falling over themselves to interview, especially as he is hugely concerned with the attack on citizens’ rights. Instead, as he has just explained, he appears to have been blacklisted.

Market commentator blacklisted

Following a recent article in influential Washington publication The Hill by cultural property lawyer Rick Mr. St. Hilaire – no friend of the market over the years – Tompa found his own comments on the issue barred.

“The Hill Newspaper refused to publish this comment, supposedly because it violates their ‘community standards’,” he explained.

“Also, Mr. St. Hilaire disallows comments on his posts, except for people he is already connected with. So, here it is.” What Tompa explains, but The Hill did not, was that St Hilaire “is associated with an archaeological advocacy group that has received substantial State Department funding as a ‘soft power measure’”.

Among Tompa’s disallowed expert critique of St Hilaire’s comments was the following: “The major issue with his punitive approach is that it seeks to enforce confiscatory foreign laws here and assumes that even common items like historic coins purchased from legitimate markets in Europe are ‘stolen’ if they don’t have a long document trails proving ‘licit’ origins. Due process for American citizens should be the utmost consideration. Not using criminal law to threaten collectors on behalf of foreign governments, particularly authoritarian regimes in the Middle East which declare anything old State property.” Tompa goes on to explain how he then tried another version, complete with citations, but The Hill wouldn’t publish it, either.

“On reflection, perhaps that’s not all that surprising because The Hill has rejected other opinion pieces from me in the past (including the one quoted at the end that was ultimately published by the American Bar Association) and others representing collector interests. Meanwhile, the Antiquities Coalition and others with similar views seem to get what they want published in The Hill Newspaper. In any event, judge for yourself if this post violates ‘community standards’ or if it’s just another case where the views of collectors and the trade are being suppressed by a ‘woke’ press.”

And in a final challenge to The Hill, he adds: “If you are really interested in a conversation you will publish this comment. As archaeologists claim, context is important.”

Whatever the media’s reason for failing this challenge, from a journalistic perspective it makes no sense to duck what is really a sensational story of widespread collusion and apparent corruption at the heart of the State. Does no one want a Pulitzer Prize anymore?

by ADA | Nov 25, 2025 | Views |

Dispute shows that the ‘moral’ case is not always clear cut

Passed as part of the Charities Act 2022, measures that have been suspended relating to deaccessioning in museums and the return of objects to source countries will now come into force.

The idea is to make it easier for institutions to return disputed objects on moral grounds. This is not as easy as it might seem, however, as different moral codes apply depending on who and where you are.

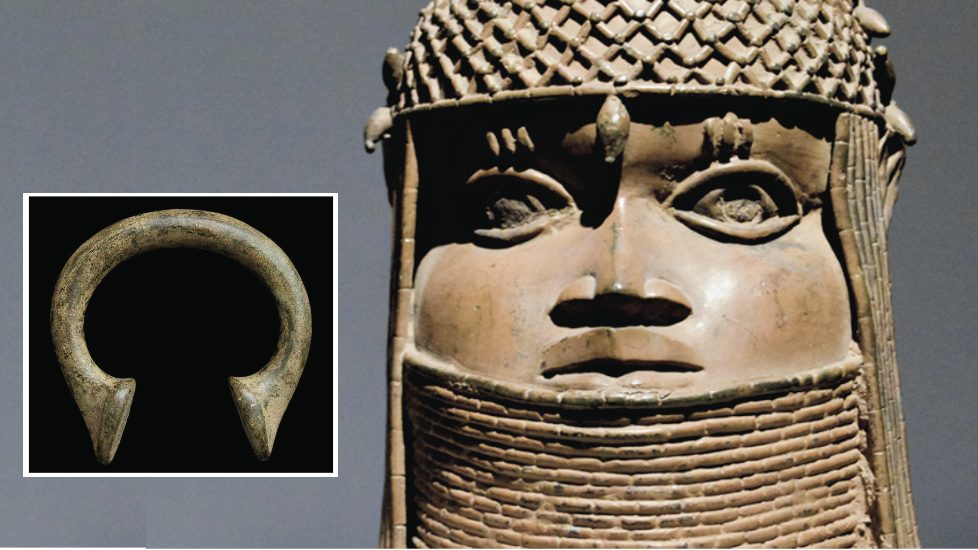

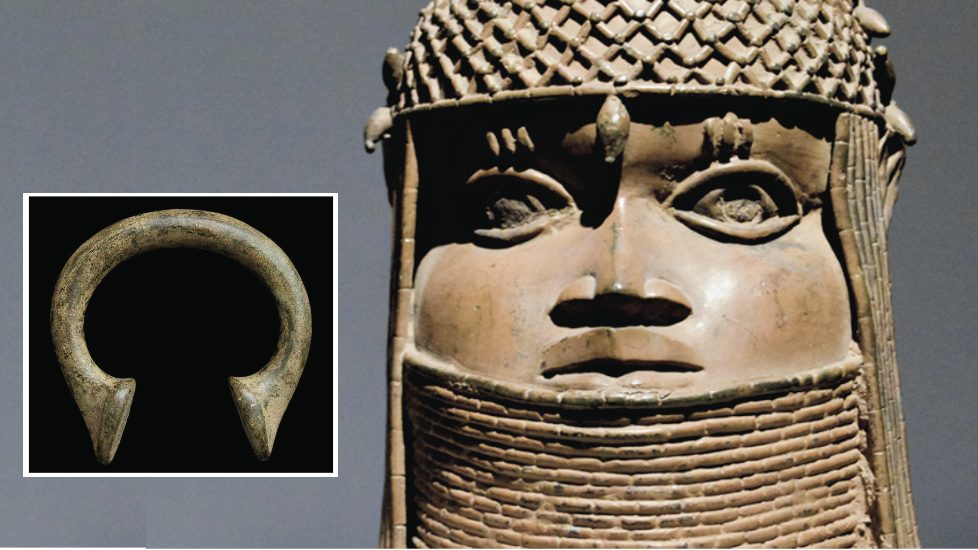

Evidence of this can be seen in the Horniman Museum’s return of Benin Bronzes to Nigeria in 2021, under earlier legislation. While the moral grounds for sending the bronzes back were their status as looted items from the British punitive expedition of 1897, the museum ignored the fact that they were the product of slavery – literally so as they were made from slave currency – which had enriched the Oba of Benin.

As the BBC revealed on November 13, however, the bronzes that have been returned have sparked widespread controversy. This is firstly because the Nigerian government has handed them over to the current Oba, thereby rewarding the direct descendant of one of Africa’s worst slavers. The descendants of former slaves in the US had protested through the courts against the return of bronzes from The Smithsonian, but lost their case because, as the bronzes had already been returned, the court decided it lacked jurisdiction in the matter.

The Oba’s links to the history of slaving have been entirely expunged from the record in Nigeria and are largely overlooked by the world’s media and those who have pressed for repatriation, but that does not mean they have been forgotten.

New museum remains shut as Oba launches legal case

Now the bronzes’ new home, the much-anticipated Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) due to open in Benin, the capital of the Edo region of Nigeria, remains shut. Its construction and fitting out has taken five years, and the idea is for it to provide jobs and boost the local economy. Funded to the tune of $25 million by British Museum fund-raising donations, among others, it has found itself at the centre of a political storm for various reasons, with permission for the land to be used to build the museum now revoked.

“Much of it comes down to internecine rivalries at a local state level, as it was Edo’s previous governor Godwin Obaseki – whose term in office ended last year – who was a major backer of the museum,” the BBC reports.

“And it seems the administration of the new governor, a close ally of the local traditional ruler, known as the Oba, may want more of a stake in the project. The protesters on Sunday, for example, were demanding that the museum be placed under the control of Oba Ewuare II.”

True enough, as it turns out, according to the Benin media, which reported on November 24 that the Oba is attempting to wrest control of the returned artefacts and any fund-raising operations linked to them by suing the museum promoters and demanding that neither the museum nor anyone else should be dealing in Benin artefacts without his permission.

“According to available court documents, the claimant is contending among others, that the Oba of Benin, being the sole custodian of the culture, tradition and heritage of the Benin Kingdom, is the only rightful person to determine where the returned looted artefacts and other items of Benin heritage should be kept,” The Benin Sun reports.

The Oba is calling for the court to declare him the sole owner, custodian and manager of repatriated looted Benin artefacts.

He is also demanding that no one else – neither individual nor institution – should be able to raise funds from outside Nigeria in his name, and he wants a perpetual injunction “restraining the defendants, their servants, privies or agents from establishing, opening and operating any museum in Benin City, Edo State, dealing with Benin artefacts without the consent of the Oba of Benin”.

One rule for the governor, another for the Oba, when it comes to family connections

In May 2023, Cambridge University’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology delayed the return of 100 of the bronzes when it feared that they would not be put on public display after outgoing President Muhammadu Buhari decreed that the Oba was the rightful owner of all returned Benin Bronzes and was responsible for the management of all places where the artefacts were kept.

One of the curious aspects to the internal political disputes over the issue in Nigeria has been the objection to former Edo state governor Obaseki, who was behind the establishment of MOWAA. The objection rests on the fact that he is the direct descendant of a palace official who was appointed as prime minster by the British after the 1897 punitive expedition. If such a direct link would disqualify him from involvement, why is the same standard not applied to the Oba himself following his forebears’ bloody past?

Clues come from reporting on the Restitution Study Group, which has led the campaign to retain the bronzes in public institutions within the United States: one argument is that while the manilla slave currency was indeed used to make the bronzes, some of it came from trading other goods, so it is impossible to say which was which. Another is the view shared by Nigerian art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu, a professor at Princeton University and an activist at the forefront of the campaign to return looted artwork. He dismissed the Restitution Study Group’s leader, Ms Farmer-Paellmann’s comments as sounding “like the arguments that white folks who don’t want to return the artefacts have made”. Whether this is true or not, he does not address the historic Obas’ role in sending more than 100,000 people into slavery down the years.

What will the governments and museums around the world, so keen to hand back the bronzes for public benefit, do now?

- Image top: A Benin bronze, and (inset), a manilla, probably made from a brass composite (Ashmolean Museum). The name comes from manilha, the Portuguese word for a bracelet.

by ADA | Oct 29, 2025 | Views |

Artificial Intelligence is undoubtedly useful, especially when carrying out research, but it is also a minefield of fake news if you don’t do your homework properly.

As an example, take a report inspired by the recent dramatic theft of Royal jewels from The Louvre and published by Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Titled Lessons from The Louvre, it includes the following statement: “Organized crime groups are increasingly targeting art and antiquities held in European collections, drawn by the continent’s cultural repositories and art markets.”

Whether this claim is true or not, the article provides no supporting evidence. It does mention a series of crimes that have taken place within Europe in recent years that may have been – even probably were – carried out by criminal gangs. Two of those mentioned even involved antiquities, although the rest did not. What they do not prove in any way is the veracity of the statement about such crimes being on the increase in Europe.

Now comes the A.I. part.

As an experiment, the Antiquities Forum asked A.I. the following question: “Is it true that organized crime groups are increasingly targeting art and antiquities held in European collections, drawn by the continent’s cultural repositories and art markets?”

The response was unequivocal: “Yes, organized crime groups are increasingly targeting art and antiquities held in European collections. The continent is a key hub for the illicit trade due to its wealth of cultural artifacts and active art markets, which organized criminals exploit for profit and other illicit purpose.”

It then provided a series of paragraphs under the heading Key reasons for the increase.

This all looked very convincing until further investigation showed that the conclusions were based entirely on sources including the article mentioned above, where significant claims had been made but without giving the evidence to show they were true.

Checking out the sources

In fact, in the case of the headline claim about organized criminals increasingly targeting European collections, the top three sources quoted were:

Further sources include a 2022 European Union Action Plan against Trafficking in Culture Goods. Its claims that trafficking is a ‘lucrative’ business and that “increasing global demand from collectors, investors and museums” is driving looting and trafficking are based on the existence of UN Security Council resolutions, the size of the legitimate art market and estimates by Europol.

The problem here is that UN Security Council resolutions are preventive measures based on perceived risk rather than on evidence of actual crime; the size of the legitimate art market (which has been shrinking in recent years, not growing) sheds no light at all on crime levels, let alone showing that they are rising; and, at its own admission, Europol has no data to support the claim made on its behalf, despite all the headline figures on arrests and seizures (but not convictions or confirmation of the goods being illicit) relating to Operation Pandora and the rest.

In other words, as is almost always the case with such claims from the EU, they are not based on facts, but on supposition.

How the claims just don’t stack up

It’s a similar tale with Interpol, whose Cultural Heritage Crime page also features as an A.I. source in this context. There Interpol’s significant (but unsupported) claim is: “Trafficking in cultural property is a low-risk, high-profit business for criminals with links to organized crime. From stolen artwork to historical artefacts, this crime can affect all countries, either as origin, transit or destinations.”

In fact, not one of the sources given by A.I. to support the robust (but misleading) conclusions it comes to stand up to scrutiny.

Unfortunately, as reports from many sources have shown, researchers looking for confirmation of their suspicions when it comes to the international art market often fall victim to confirmation bias, failing to check the sources they cite through footnotes and embedded links because on the surface they seem to support what they believe.

Because of this, it has been surprisingly easy to debunk long accepted, but false, claims about the art market. And it also explains why the Antiquities Dealers’ Association (ADA) and the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA), who between them support the work of the Antiquities Forum, for years have operated a policy of checking primary sources for claims wherever possible.They provide those sources wherever possible in promoting their own views and arguments, and ask their audiences to check the sources given for their own satisfaction. Unfortunately, this is a highly sensitive and controversial arena where no one – no matter who they are – can simply be taken at their word. And A.I. is not going to fix that any time soon.

by ADA | Oct 27, 2025 | Views |

The latest news on the repatriation front is that the United States is working on a plan to send a major archive back to Iraq.

Shafaq News reports: “Minister Ahmed Fakkak Al-Badrani told Shafaq News that the Iraqi government is maintaining “continuous coordination and diplomatic engagement with US authorities to secure the archive’s return,” adding that joint committees involving Iraq’s security agencies, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs are working in coordination with the US Embassy in Baghdad to follow up this issue.

If that all sounds straightforward, it isn’t, and the reason is that the archive in question is the Jewish Archive currently kept in Washington.

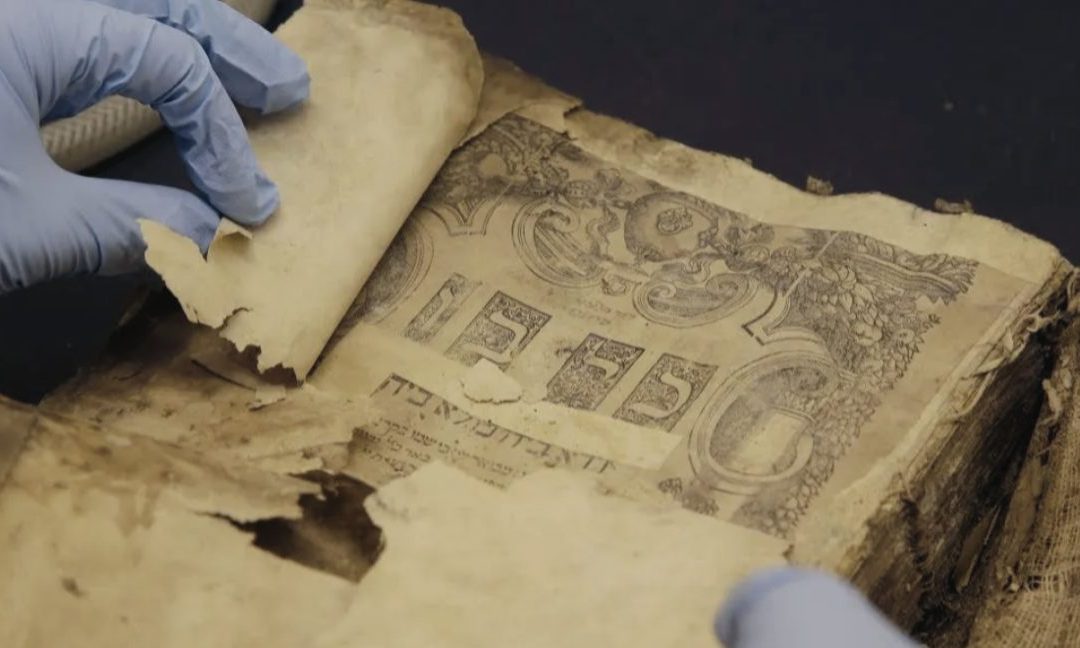

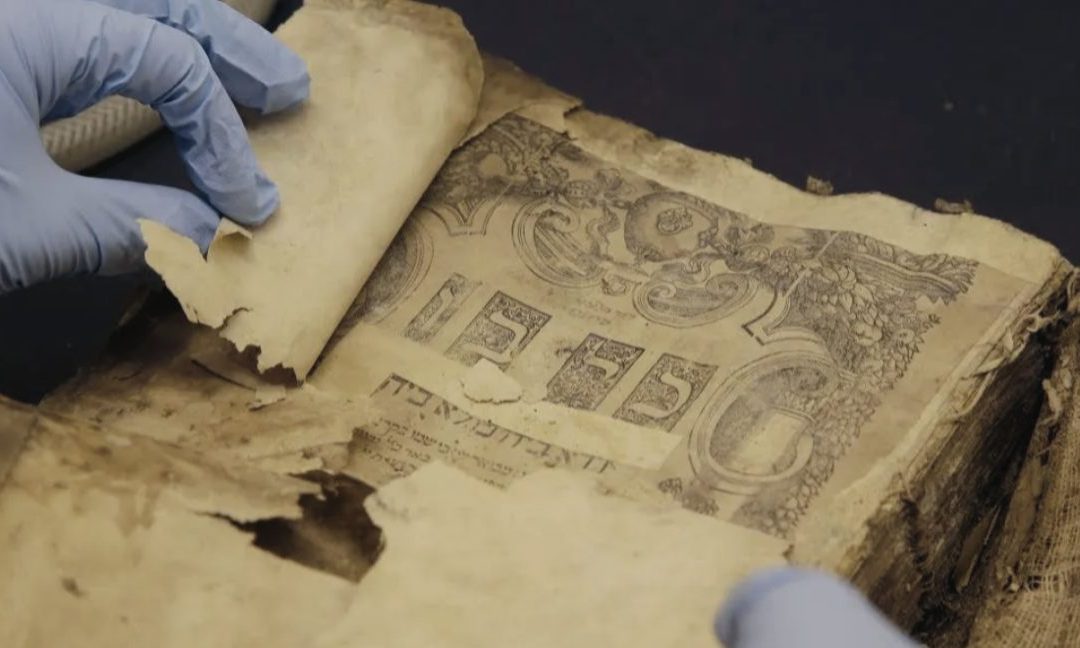

It includes thousands of historical documents, religious texts, and personal records belonging to Iraq’s Jewish community: Torah scrolls, rare manuscripts dating back to the 16th century, a 400-year-old Hebrew prayer book, a 200-year-old Talmud volume, a 1902 Passover prayer book (Haggadah), and French-language prayer texts from 1930.

“It also features printed sermons from a German rabbi dating to 1692, along with school records spanning 1920–1975,” reports Shafaq News.

Also known as the Iraqi Mukhabarat Archive, it came to light in 2003 when a 26-member US “Alpha” unit operating in the country found it in the basement of Iraq’s former intelligence headquarters during a search for evidence of mass destruction weapons.

Seen as an important repository of information about the Jewish community that flourished in Iraq for 2,500 years, the repatriations would seem a fitting solution… except for the fact that almost all the Jews fled Iraq in the mid-20th century after being stripped of their citizenship and assets. The archive was in the basement because it had been stored there after being seized by the authorities.

In light of this, one can understand the calls from scholars and Jewish groups who have said that the US should instead send the archive to Israel.

Unanimous Senate vote started the process

Nonetheless, a unanimous Senate vote of 2014 passed a resolution calling on then President Barack Obama to reopen new negotiations on returning the archive to Iraq. Pending the outcome of those talks, it was agreed that the archive would remain in place until 2018, after which a further delay was set in place.

The US appears to think it has a contractual obligation to send the archive to Iraq, but not everyone agrees.

Back in 2013, Stanley Urman, executive vice president of Justice for Jews from Arab Countries (JJAC), cited“jus ex injuria non oritur”, a legal principle in international law arguing that a state cannot assert legal rights to property it has obtained illegally.

“[The materials] were seized from Jewish institutions, schools and the community,” he explained. “There is no justification or logic in sending these Jewish archives back to Iraq, a place that has virtually no Jews, no interest in Jewish heritage and no accessibility to Jewish scholars.”

Whichever way you look at the issue, the whole concept of repatriation is based on a sense of restorative justice, a common theme among all the speeches and media releases that accompany returns from the US via bilateral agreements and other mechanisms.

As with the recent return of Tibetan artefacts to the occupying forces of China, the idea of sending the Jewish archives back to the country that persecuted and effectively expunged its Jewish population is no less than an insult to the oppressed and a reward for oppression. The US needs to review its shameful policy now.

by ADA | Sep 18, 2025 | Uncategorized, Views |

In 2001, the Taliban took 25 days to blow up the extraordinary and important Bamiyan Buddhas – two ancient monumental cliff carvings in Afghanistan that were the largest standing statues of their type in the world.

It was as much a political as religious act of cultural vandalism by iconoclastic extremists who were demanding recognition and the acknowledgement of Islam’s pre-eminence in a country with a Buddhist tradition.

Who would have thought that less than a quarter of a century later, it would become official policy for the United States to repatriate Afghan cultural property to the Taliban, now the oppressive government of a people it subjects to innumerable human rights abuses on top of the cultural nihilism?

But that is exactly what is happening now in the name of U.S. citizens, and it is far from an isolated case.

This state of affairs is all part of a wider move by authorities in the U.S. and elsewhere to harness cultural heritage as a low-cost and highly useful soft power diplomacy tool. Help other countries recover artefacts that were either stolen or sold off legally before passing beyond their borders and it can assist power brokers such as the U.S. to boost their geopolitical influence in trouble spots where unwelcome rivals such as China and Russia may be gaining a foothold.

It may be a cheap and effective political tool, but where are the ethics and morals of such a policy, and who loses in the process?

A recent case involving the Manhattan District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit sheds light on this.

Chinese or Tibetan?

As reported in March 2025, the unit, under the command of Assistant D.A. Matthew Bogdanos, handed over 41 artefacts to China on March 3. The problem is that the artefacts were not Chinese but Tibetan.

“The transfer was conducted as part of an agreement between the two countries to protect cultural heritage and identity and prevent Chinese cultural relics from illegally entering the U.S.,” reported Radio Free Asia. “Since the pact was first agreed to on Jan. 14, 2009, the U.S. has sent 594 pieces or sets of cultural relics and artworks to China.”

Returning cultural property to the oppressors of those to whom they should actually belong rightly raises concerns: “…sending Tibetan artifacts to China has raised concern that Beijing will use them to justify its rule in Tibet, which the country annexed in 1950,” RFA argues.

This view was echoed by Vijay Kranti, director of the Center for Himalayan Asia Studies and Engagement, based in New Delhi, who told the RFA: “The Chinese government will certainly misuse these returned artifacts and will use them to further promote their false historical narrative that Tibet has always been a part of China.”

Kate Fitz Gibbon, executive director of the Committee for Cultural Policy, the U.S. think tank established in 2011 to strengthen the public dialogue on arts policy, was equally critical.

“It is an outrageous act to return Tibetan objects in the diaspora to the People’s Republic of China, which is deliberately destroying Tibetan cultural heritage,” she said.

“Since China occupied Tibet, U.S. authorities have accepted that Tibetan artifacts belong to the Tibetan people, not China’s government,” Fitz Gibbon said in an email. “The turnover by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit directly challenges that policy.”

It is certainly an odd move when the D.A.’s office and ADA Bogdanos spend so much time declaring their dedication to righting historic wrongs.

What Memoranda of Understanding mean

If the Manhattan D.A. uses New York State law relating to theft to pursue its seizures and returns, the U.S. State department and Customs service take advantage of an ever-expanding system of bilateral agreements, also known as Memoranda of Understanding.

These allow law enforcement to bypass international conventions and human rights laws and conventions, giving them the authority to seize almost anything historic that originated in the country of an MoU partner, before handing it over to them. No evidence of the item in question being illicit is required. This is hardly in the spirit or terms of the United States Constitution.

As an example, consider the MoU with Turkey, which is up for renewal. Article 1 of the MoU restricts the import to the U.S. of a comprehensive list of archaeological material ranging in date from 1.2 million years BC to 1770 AD, and a similarly extensive list of ethnological material ranging in date from the 1st century AD until 1923.

Essentially, anything that falls into either of these categories – pretty much everything – will be seized at the U.S. border as it is imported and returned to Turkey unless it already has a valid export license from Turkey or Turkey agrees to issue it with a licence saying that its original export from Turkey did not violate local laws.

Effectively, then, the U.S. has handed a veto to a third country over legally held property that allows for its confiscation without proof of wrongdoing. Under such circumstances, this interference with an individual’s right to enjoy their property can easily be assessed as arbitrary – and therefore a direct breach of Article 17.2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The problem is that the UDHR is not a binding treaty, but the United Nations does consider that its member states, which include the U.S., have a moral obligation to respect the fundamental human rights in the Declaration. However, as this issue shows, they don’t. Constitutional rights also appear to have been cast aside here.

Turkey or Armenia?

The MoU with Turkey is highly relevant now as the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC), which officially advises Congress, considers its renewal and update.

Objections to its standing terms have come from the Armenian Bar Association and the International Association of professional Numismatists (IAPN).

The Armenian Bar Association is concerned that without its proposed amendments to the MoU, Turkey may lay claim to Armenian cultural artefacts that predate the arrival of Turks in the Armenian homeland which is now part of modern Turkey. “Equally perverse, Turkey may argue that Armenian cultural property currently located in the United States, which originated on the land mass of current-day Turkey, belongs to Turkey as well and, therefore, must be repatriated,” it argues.

Likewise, the International Association of Professional Numismatists (IAPN) has raised objections to the renewal of MoUs with Afghanistan and Turkey. IAPN Executive Director Peter Tompa set out the association’s detailed objections in his Cultural Property Observer blog, arguing that for both countries, “renewals raise fundamental contradictions that cannot possibly be reconciled”.

In tune with the Armenian Bar Association, Tompa also objects to a renewal of the Turkey MoU on the grounds of Turkey laying claim to the cultural heritage of minority groups within its borders: “Erdogan’s aggressive repatriation efforts abroad must be contrasted with his government’s active promotion of ‘treasure hunting’ at former Jewish and Christian sites at home. This is just another provocation directed at minority religious groups like the conversion of Hagia Sophia and the Cathedral at Ani into mosques,” he writes.

Tompa had previously raised concerns about Jewish artefacts being returned to the Libyan government that had expelled the Jews.

Libya or the Jews?

“Jewish groups are outraged and say the MoU legitimizes the confiscation of Jewish property seized by Libya’s government when they were forced from the country,” Tompa wrote in 2018. “Others in the cultural policy world are wondering why the US government would put faith in Libya to act responsibly to safeguard the heritage of minority and exiled peoples.”

Add to all this the fact that many of those regimes with whom the U.S. establishes these bilateral agreements are not only lacking in democratic principle, but actively hostile to the U.S., and the injustice burns all the brighter.

Tompa has also written in-depth in Cultural Property News on how MoUs work and what they mean.

How aware are U.S. citizens that their own State department and Customs service are acting like this in their name or that they might find their own property subject to such confiscation? And how would they feel about it, particularly if their own legally held property was seized in this way? Will CPAC do the right thing in advising Congress?

Image caption: US Ambassador to Turkey David Satterfield and Turkish Minister of Culture and Tourism Mehmet Ersoy sign an MOU on cultural heritage, effectively acknowledging Turkish government control of minority religious communities’ heritage. Photo Credit: US Embassy in Turkey

Recent Comments