by ADA | Jan 30, 2024 | Uncategorized, Views

Sources quoted by authorities to clamp down on the art market rarely stand up to scrutiny

How does false data come to influence policy and even law making on such a widespread basis when it comes to cultural property?

One reason is confirmation bias: if the results of your research match what you hope to find, you are less likely to check their validity – a point made by statistics guru Dr Tim Harford when discussing claims made about antiquities and crime.

Another can be the authority of the source. This is very common in the cultural heritage sphere.

This two-part article analyses two studies from what should be an impeccable single source, showing how false data can spread from one official report to another to gain traction, and ultimately become an unchallenged authority among those who should know better.

They also demonstrate that many apparently learned pieces of research published by acknowledged authorities simply can’t be trusted, because it is clear that these professionals are not checking their sources adequately.

Both reports were published by the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

One was titled PRACTICAL ASSISTANCE TOOL to assist in the implementation of the International Guidelines for Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Responses with Respect to Trafficking in Cultural Property and Other Related Offences. It was published in 2016.

The two relevant claims it included were as follows:

• The Museums Association has estimated that profits from the illicit antiquities trade range for $225 million and $3 billion per year.

AND

• The Organized Crime Group of the United Kingdom Metropolitan Police and INTERPOL has calculated that profits from the illicit antiquities trade amounted to between $300 million and $6 billion per year.

Footnotes indicated the source for each of these statements.

For the first it was “See Neil Brodie, Jenny Doole and Peter Watson, Stealing History: The Illicit Trade in Cultural Material (Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2000); and Simon Mackenzie, “Trafficking antiquities” in International Crime and Justice, Mangai Nataajan, ed. (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2011).”

For the second it was “United Kingdom, House of Commons, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee, Cultural Property: Return and Illicit Trade, seventh report, vols. 1, 2 and 3 (London, 2000).”

These were very precise references, if rather out of date for a 2016 report by the UNODC.

The problem is that whoever researched the UNODC report failed to check where its quoted sources got their data from. If they had, they would have found the following:

– The Brodie, Doole and Watson report from 2000 did not refer to the Museums Association $225 million and $3 billion per year claim at all. Instead, on page 23 in the introduction to section 1.9, The Financial value of the illicit trade, it stated: “Geraldine Norman has estimated that the illicit trade in antiquities, world-wide, may be as much as $2 billion a year.” The footnote for this statement identified the source as journalist Geraldine Norman’s November 24, 1990, Independent article Great sale of the century. However, apart from the fact that the article was actually titled Great sale of the centuries, it included no such claim or figure.

The Simon Mackenzie chapter on Trafficking Antiquities is not open source data, but is available on subscription to CUP.

– In fact, the Museums Association did give estimated figures as part of its evidence to the UK House of Commons, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee, Cultural Property: Return and Illicit Trade, seventh report, vols. 1, 2 and 3 (London, 2000) – the same source as the second claim quoted by the UNODC. In the Seventh Report, Chapter II The problem of illicit trade, The nature and scale of illicit trade, paragraph 9 reads: “The scale of the illicit trade taken is said to be very considerable. According to the Museums Association, as an underground, secretive activity, it is impossible to attach a firm financial value to the illicit trade in cultural material. Estimates of its worldwide extent vary from £150 million up to £2 billion per year.” The Museums Association gave as its source the Brodie, Doole and Watson 2000 report, quoted above, which in turn gave the Geraldine Norman article as the source, when, in fact, it provided no such figures.

So, the Museums Association’s actual claim was that “it is impossible to attach a firm financial value to the illicit trade in cultural material”, but that estimates worldwide [by others] varied greatly between £150 million and £2 billion.

This was rather different from the UNODC claim based on this source: “The Museums Association has estimated that profits from the illicit antiquities trade range for $225 million and $3 billion per year.”

To summarise, then, the £150 million to £2 billion claim ultimately came from nowhere. Its claimed primary source, the Geraldine Norman article from 1990, quoted no such figures. The secondary source which mistakenly quoted them was the Brodie, Doole & Watson report from ten years later in 2000, leading to the tertiary source of the Museums Association. In turn, this was quoted by the UNODC in 2016 – 26 years after the Norman article which gave no figures anyway. The UNODC report then became a new ‘primary’ source, with the figures quoted as UNODC estimates, which they weren’t at all.

See Part 2

by ADA | Jan 30, 2024 | Views |

Decades-old inaccurate figures used to promote tighter anti-money laundering policy

Of more immediate interest is an older UNODC report, Estimating Illicit Financial Flows Resulting from Drug Trafficking and Other Transnational Organized Crimes, from 2011. It is relevant now because in February 2023, the Financial Action Task Force report: Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in the Art and Antiquities Market quoted it to support its analysis that money laundering risk was high. Now the European Union is using the FATF report to develop further AML policy.

On page 36 of the UNODC’s 2011 report, it gave a value range of $3.4 billion to $6.3 billion as the Global Financial Integrity (GFI) estimates of the global proceeds of crime for art and cultural property, based on information from Interpol and the International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council (ISPAC) of the UN Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme.

The UNODC report stated that its Interpol and UN-related figures came from the February 2011 Global Financial Integrity (GFI) report, Transnational crime in the Developing World, and World Bank indicators (for current GDP).

Page 47 of the GFI report included a section headed Estimated Value of the Illicit Trade of Cultural Property, which began: “The actual value of the global illicit trade in cultural property is unknown and most experts are hesitant to estimate a value.”

Despite this, the UNODC provided an estimate range of $3.4-6.3 billion for the proceeds of transnational crime involving art and cultural property, citing the GFI report “based on Interpol, International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council of the United Nations Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme”.

The remainder of that opening paragraph from the GFI report explained where this range of figures came from: “Estimates that do exist range in size from $300 million to $6 billion per year, with Interpol estimating $4 to $5 billion,and the International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council of the United Nations Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme (ISPAC) estimating $6 to $8 billion. This report creates a range by taking the average of the low estimates and the average of the high estimates reported above. The result is an annual value of $3.4 to $6.3 billion.”

Checking the sources of these sources we come up with the following:

– $300 million to $6 billion: Not stipulated, but almost certainly from the UK House of Commons, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee, Cultural Property: Return and Illicit Trade, seventh report, vols. 1, 2 and 3 (London, 2000) (see Part 1 of this article), where they were quoted anecdotally by a Scotland Yard office whose colleague then provided evidence to refute them.

– $4 billion to $5 billion: Currently unavailable

– $6 billion to $8 billion: the International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council of the United Nations Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme. ISPAC (2009). Organized crime in Art and Antiquities. Selected Papers from the international conference held at Courtmayeur, Italy 12-14th December 2008. Milan: ISPAC.

UNODC Deputy Director John Sandage wrote the foreword to the published ISPAC paper from that 2008/9 programme. Its second paragraph read: “The value of international trade in looted, stolen or smuggled art is estimated at between US$4.5 billion to US$6 billion per year.”

Page 30 of the same report cited a figure of $7.8 billion from The 1999 United Nations Global Report, but it was wrong. In fact, the 1999 UN report quoted the range of $4.5 billion to $6 billion (see page 229), attributing it to a New York Times article of November 20, 1995, by Alan Riding titled Art theft is booming, bringing an effort to respond. Riding proved to be a dead end, giving no source beyond “experts”.

Meanwhile, Page 31 of the ISPAC report quoted a figure of £3 billion for London in the early 1990s according to Scotland Yard, and FBI figures of $5 billion and $6 billion for the whole art theft market for 2008.

In total then, the estimated $6 billion to $8 billion figures quoted by the UNODC in 2011 appear to come from a mix of sources, including the FBI and a non-existent rounded up figure from the 1999 United Nations Global Report. The FBI did not give a source for its figures, while the 1999 UN report gave a different range of figures, sourced from a 1995 New York Times article whose only source is unnamed experts.

As they refer to the “art theft market”, they clearly include all associated crime, such as commercial and domestic burglaries, with associated insurance losses – as can be seen from the evidence provided by Scotland Yard to the House of Commons in 2000 – and the ISPAC report confirmed that Interpol attributed the highest levels of cultural property theft to Italy and France.

Now move forward to 2023 and the Financial Action Task Force report, entitled Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in the Art and Antiquities Market, and the $6.3 billion figure arises once again in paragraph 3 of the Introduction on page 5. The FATF burnishes that figure by stating that it is a UNODC estimate, whose own source (the 2011 report) shows that this is not true. In reality, it is a figure quoted by the UNODC from other uncertain and inaccurate sources, as shown above.

So, a report by the FATF published in February 2023, aimed at influencing current international policy – and now being used by the EU to tighten its anti-money laundering regulations further – quotes a 12-year-old set of figures based on guestimates and unattributed sources dating from the early 1990s to 2008. And it uses this as the key statistic relating to current global art crime to make its point.

As can be seen by the tortuous byways of out-of-date reports and newspaper articles dating back almost 35 years and quoting myriad figures that have contributed to this misleading picture, the truth can be lost very quickly. Nonetheless, the authority of the UNODC means these statistics are quoted as key evidence.

And this is just one example of how this is happening.

See Part 1

by ADA | Jan 4, 2024 | Views

The cheap and easy way to gain diplomatic influence can cost individuals and vulnerable groups dearly

Cultural heritage Memoranda of Understanding are good for diplomacy but can damage the rights of citizens

As anyone from the art market involved in the international world of cultural heritage will know, dealers, auction houses, buyers and sellers have long been the unjustified targets of governments, NGOs and law enforcement.

The message has been that the looting and trafficking of cultural property from vulnerable nations – many of whom are in an almost permanent state of crisis or war – is funding terrorism. Stolen items smuggled to Western markets lead to a flow of cash in the other direction to pay for bombs and bullets, they argue.

The problem is that despite innumerable research projects, studies and other initiatives to show this over the past 20 years and more, evidence of the art market’s role in this is so thin on the ground as to be all but non-existent.

Independent studies, such as the ground-breaking RAND Corporation report of 2020, state that open source evidence clearly demonstrates that the antiquities market could not possibly sustain the billion-dollar level of international crime it is accused of fomenting.

This has not prevented bodies like the European Union, the United States Government and others competing for influence in strategically important countries like Egypt, Iraq and Syria from introducing proposal after proposal – so numerous that they seem to be falling over each other for precedence – to tackle the perceived problem.

Campaigner highlighting injustice

Collector and cultural property lawyer Peter Tompa has been at the vanguard in highlighting abuses of power and influence when it comes to policy in this field.

His latest article, published by Cultural Property News, shows how the US State Department has been harnessing bilateral agreements (Memoranda of Understanding) involving works of art and ancient artefacts to curry favour in geopolitics. In doing so, it is acting against the will of Congress and against the interests of private citizens, including vulnerable ethnic and religious groups, he believes.

At the heart of the problem is the fact that MoUs effectively reverse the burden of proof over the ownership of cultural property at the point of import; you’re guilty until deemed innocent. Importers to the United States must secure a current licence from the source country covered by the MoU confirming that the imported item in question was originally exported legally from there, whenever that might have been – and it could have been centuries ago.

So, this would apply to a Roman vase that could have left Italy during the 18th century, having been purchased by a wealthy young man on the Grand Tour, and has since changed hands and moved countries numerous times. How likely is it that the current importer would hold paperwork from that original sale and export that would convince the Italian authorities to issue such a licence? But that is what Article 1 of theMoU with Italy stipulates if Customs are not to seize the vase and send it back to Italy.

Similar agreements are in place with 30 other nations, from China to Yemen.

Tompa has previously highlighted the fact that MoUs can also deprive vulnerable minority groups, such as the expelled Jews of Libya, of their moral and legal rights in reclaiming their cultural patrimony. Instead, under the terms of the MoU, objects are returned to these peoples’ oppressors in the states from which they have been expelled or subjugated.

So, how can the State Department justify this rapid spread of these agreements?

Lack of funding for archaeologists has forced many of them to earn a living doing something else, Tompa notes. “Thanks to government largess, however, lucrative new opportunities have arisen for a select few archaeologists working with State Department bureaucrats to help justify cultural property Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) or “emergency import restrictions.”

‘Jihad against private ownership’

For many, this is an easy choice to make: “Not surprisingly, such work often draws those most committed to the view that cultural artifacts should be clawed back from U.S. collectors and museums for the benefit of countries that have been victimized in the past by Western colonialism. Most collectors, dealers and museum curators have no idea about all the State Department money that is funding this jihad against the private ownership of cultural goods in the U.S.”

Tompa looks at who is running what he describes as a “cottage industry”.

“The U.S. State Department Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA) and its Cultural Heritage Center have done more than anyone to grow this new cottage industry through grants and contracts as part of their ‘soft power’ efforts that seek to make hostile third world governments ‘like us more’,” he writes.

He also explains how the State Department circumvents restrictions imposed by Congress on the former’s ability to exploit MoUs for its own ends.

As always, following the money provides a clearer picture. The State Department needs better evidence of looting and trafficking to justify MoUs. It also needs to show that recipient source countries have appropriate controls in place to protect their cultural patrimony.

Tompa notes that critics have asked how much of an incentive those being funded have to come up with what the State Department wants. He describes the long-established American Society of Overseas Research (ASOR) as a major grant recipient and “evidence maker” for some of the most difficult to justify MoUs and cites examples of how those receiving hundreds of thousands of dollars in funding may be creating false narratives to suit the State Department’s purposes.

Tompa provides several examples of concerning behaviour, in one case citing an archaeologist associated with ASOR, working under a $600,000 State Department contract, who was identified as the source for a widely reported false claim that the ISIS terror group’s profits from antiquities looting were “second only to the revenue the group derives from illicit oil sales”.

Where is the media on this?

This is explosive stuff and a potentially dream investigation for any curious journalist worth their salt, involving, as it does, vast sums of money, Washington insiders and international policy that favours countries with questionable human rights records. So far, though, both the mainstream and leading art market media outlets have remained silent, leaving experts likes Tompa to do all the heavy lifting. This is curious when one considers how frequently and keenly the widespread media reports any example (alleged or actual) of crime involving cultural property.

The harnessing of such bilateral agreements for geopolitical gain – with art traders and private citizens paying the price – has long been a subject of concern. Could fear among journalists of falling out with influential advocacy groups who act as regular story sources be the reason for their apparent lack of interest?

This hands-off approach from hacks may be emboldening the State department. Tompa writes: “The State Department acting as both decision maker and facilitator for cultural property MoUs raises other concerns. More recently, the State Department has dropped all pretense of following the intent of the CPIA (Cultural Property Implementation Act) by showering additional funding on archaeologists to facilitate new and renewed cultural property MoUs.”

What we are seeing on a widespread basis is not the development of evidence-based policy, but policy-based evidence as the stakes rise among MENA nations and in the Far East, as well as in Central and South America. Security, diplomatic influence and other issues may be the real concerns, but cultural heritage Memoranda of Understanding are the currency by which a favourable position can easily and inexpensively be achieved. While that is understandable, the conditions under which they are being issued raise serious ethical, moral – and in the case of the U.S. Constitutional – questions, particularly about the rights of citizens and vulnerable groups, as well as fundamental principles of law.

Let’s not forget that the same U.S. citizens having their goods seized are also unwittingly funding this unjust process.So far, no one in authority has made any serious challenge to this process. It is about time that changed.

by ADA | Nov 23, 2023 | Views

Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos has been head of Manhattan’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU) since 2018. He has understood since at least 2011 – and probably earlier – that claims of a multi-billion dollar market in looted and trafficked antiquities have no basis in fact. This is evident from the opinion piece he wrote for CNN, published on July 7, 2011. In that piece he wrote:

“One of the main problems with looting is that if a site is undiscovered, you simply don’t know what you don’t know. Interpol estimates that the illicit antiquities trade is worth billions of dollars. My question is: How do they know that?

“If it is illegal and, therefore, a clandestine trade, how do you know the dollar amount? It is similar to the drugs trade, you guess from the amount you’re able to seize. It is not a scientific approach, nor one I am comfortable using in assessing the total value of the worldwide trade in illegal antiquities.”

These two paragraphs additionally confirm that Bogdanos is guessing when he associates the scale and importance of antiquities trafficking with that of drugs and weapons. He even tells us that that is exactly what he is doing and that he is not comfortable with it.

If, as he argues, that Interpol – and so anyone else – cannot possibly know the value of the illicit market, it is a logical consequence that they also cannot claim that it is of equal standing in scale and scope to markets in trafficked drugs or weapons. These are simply false claims about antiquities.

Further evidence to show claims are false

Little has changed regarding such data since 2011, except that since 2015, the World Customs Organisation (WCO) has produced annual Illicit Trade Reports assessing the size and comparative extent of risk categories, including cultural heritage. Those reports include information registered via the Customs Enforcement Network (CEN) and so are not comprehensive. However, the figures for cultural heritage, of which antiquities form a miniscule part, are so small compared with other risk categories, including drugs, counterfeit goods, tax evasion and weapons, that it is clear there is no similarity at all in scale or scope between drugs and weapons trafficking, on the one hand, and antiquities trafficking on the other.

Further, the 2020 RAND Corporation report, an independent study into open source data on the issue by what is arguably the United States’ most trusted research organisation, concluded that available evidence showed that a multi-billion dollar illicit global market in antiquities was simply unsustainable: “Simply put, while we cannot claim to measure the size of the illicit market, we can show that observable market channels are too small to act as conduits for a billion-dollar-a-year illicit trade.”[1]

That report also concluded that what had become widespread claims of the trade in illicit antiquities being linked to those in drugs and weapons could be traced back to Bogdanos as the original source.[2]

Twelve years on from publicly declaring that the multi-billion dollar claim had no basis in fact, and that the link to drugs and weapons claim was pure guesswork, we find that the Manhattan District Attorney’s office is still promoting the first claim in its media releases.

False claim repeated more than once in recent media releases

On March 21, 2023, under the headline D.A, Bragg Returns 29 Antiquities to Greece, the official media release from the D.A.’s office included the following statement: “Antiquities trafficking is a multi-billion-dollar business with looters and smugglers turning a profit at the expense of cultural heritage…”. The speaker was Special Agent in Charge for HSI New York Ivan J. Arvelo.

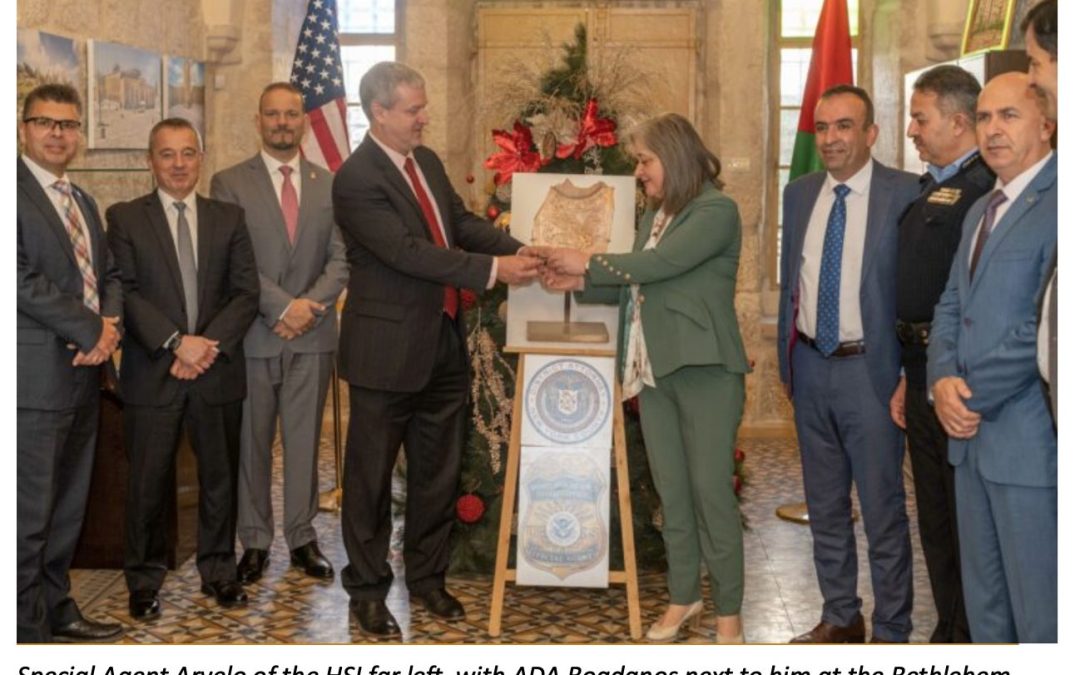

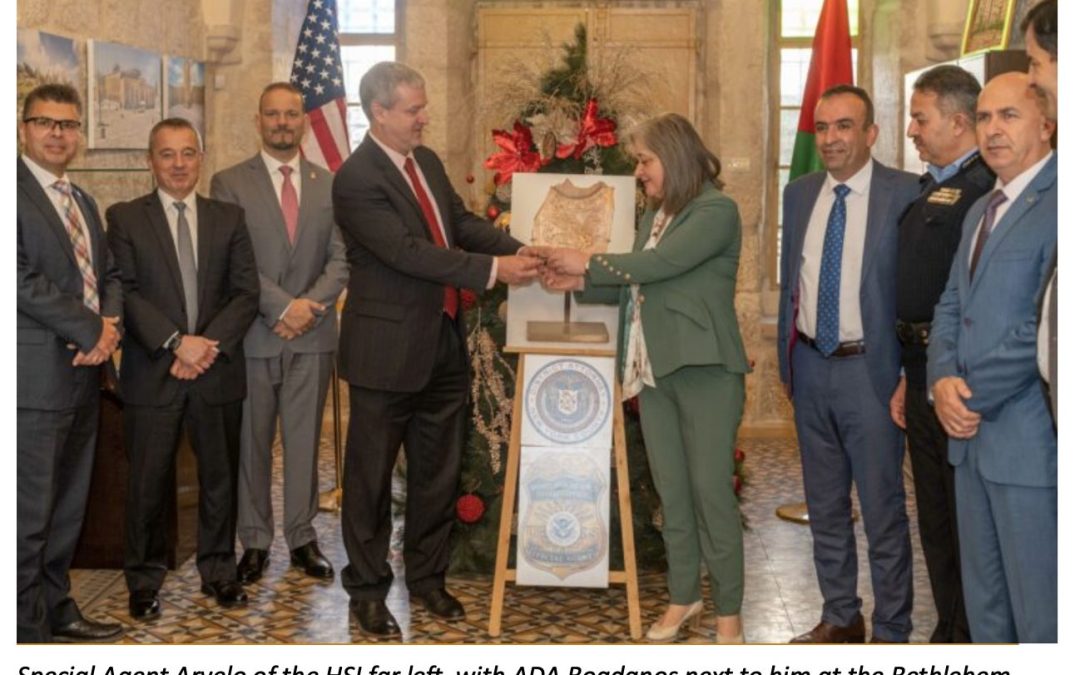

The same quote from Arvelo had been included in the D.A.’s earlier official media release on January 5, 2023, regarding the return of an artefact to the Palestinian authority. It is not clear whether Arvelo made his comment during the ceremony at Bethlehem, when Bogdanos was standing next to him, or afterwards, but it remained uncorrected in both releases.

It is hard to believe that in such a sensitive area of crime fighting official releases from the District Attorney’s office would not be scrutinised and signed off by its leading officer prior to release. If Bogdanos is not screening official releases, it raises the question as to why not. If he is, why is he not correcting what at best can be called misinformation that he is well aware of prior to their issue, or at least doing so once they have been released?

He has long known about how controversial and false these claims about antiquities are and, as in his 2011 opinion piece for CNN, expressed his discomfort with their use. Such oversight is crucial to the ATU’s credibility.

If we cannot rely on the D.A.’s office to issue accurate information relating to this highly sensitive area, how can we have confidence in the rest of what it has to tell us on this subject?

[1] See Measuring the international trade in antiquities, page 70 AND Issues with the Current Approach for Assessing the Antiquities Market to Terrorist Funding, page 12 AND Summary, page 84-85 AND Findings, page xii

[2] See Antiquities Trafficking Using Telegram, pages 49-50

by ADA | Oct 27, 2023 | Uncategorized, Views

Three developments in recent weeks have raised questions once again about the activities of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office and its antiquities unit. Separately they are of concern; together they demand some clear answers.

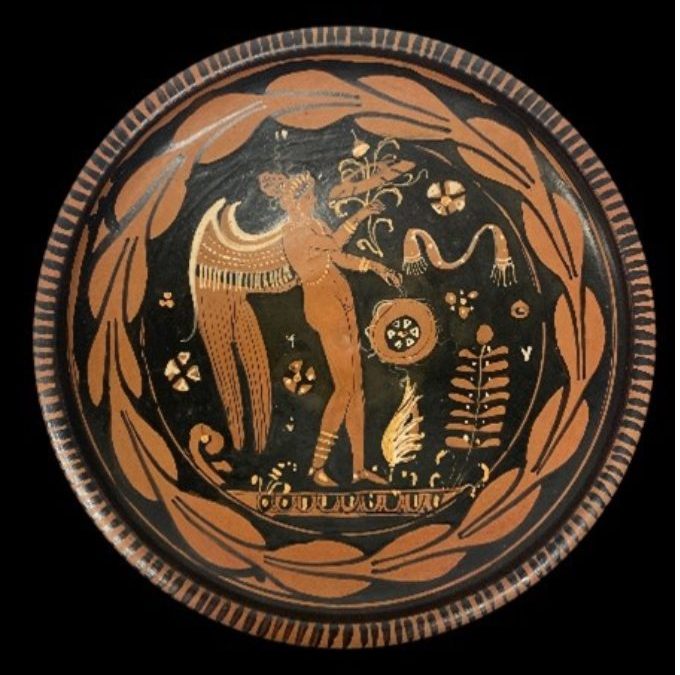

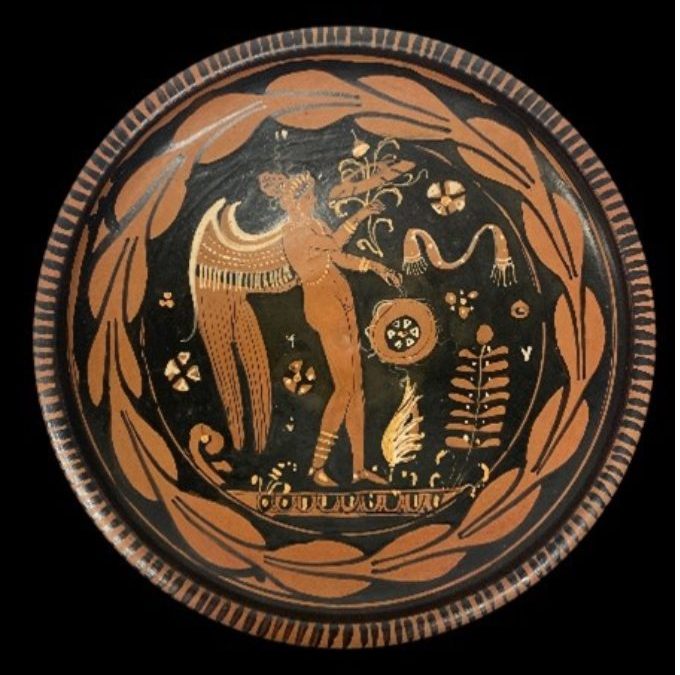

The first involves the claim that 19 items returned to Italy as “illicit” were worth $19 million. The figures simply didn’t add up according to expert valuers from the Antiquities Dealers’ Association, who noted that the South Italian plate included was worth up to about $7,000 at auction, but “only if it were to have a good provenance”.

When asked by Antiques Trade Gazette how the unit had arrived at the valuation, the D.A.’s office replied: “We have experts assess the objects at the time of each repatriation based on the legal definition of value under the law.”

Who these experts are and how they arrived at such an overblown valuation remains a mystery.

This matters because:

- What appears to be a gross exaggeration of value feeds into the inaccurate narrative of a huge international illicit trade in artefacts.

- It also boosts the public standing of the antiquities unit, which in turn makes its unquestioned position all the more unassailable at a time when serious questions regarding its activities need to be asked.

- The unit’s activities are funded from the public purse, so the public is entitled to accurate reporting and transparency.

If the above is an accurate assessment of the situation, it raises a raft of new questions.

One of those questions involves the second development: the D.A.’s publishing of a media release that led to inaccurate reporting on the criminal status of individuals.

Having unequivocally labelled a number of named individuals as “major antiquities traffickers” in the opening paragraph, an unheralded footnote states: “The charges referenced within are merely allegations, and the individuals are presumed innocent unless and until proven guilty.”

The failure to annotate the body of the release with a reference to the footnote inevitably risks misreporting, especially by those who fail to read to the end of the release. An internet search has revealed at least two examples of this happening in this case. Why is this not of serious concern to the Manhattan D.A.?

Cleveland Museum of Arts sues the D.A. over statue seizure

One of the most significant developments has come at the hands of the Cleveland Museum of Arts, which is now suing the D.A.’s office over its seizure of a headless ancient bronze statue valued at $20 million.

The D.A.’s office argues that it is of Marcus Aurelius and was looted from Turkey. The museum, which acquired the statue in 1986, says that is not the case.

As the court papers reveal, Turkey made vague and unsubstantiated claims regarding the statue around 15 years ago but did not respond when asked for evidence to support its case and did not pursue the matter further until now.

As the statue had been widely exhibited and written about over the years, Turkey had had a long time to press its case but did not do so. This was also the case when Turkey failed in its claim over the Guennol Stargazer in the New York courts. Among other comments in 2021, U.S. District Judge Alison Nathan noted that Turkey had known of the piece for years and had had ample opportunity to make a claim but had failed to do so in a timely manner.

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s court papers highlight the controversial approach of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office in seizing objects and returning them to source countries: “For more than ten years, the New York County (Manhattan) District Attorney has conducted numerous investigations of antiquities allegedly stolen from foreign nations, returning many of them to those nations. Proof that these items are “stolen” typically is established using the laws of such nations (“patrimony laws”), which, among other things, declare that items of a certain age or type belong to the nation. If a covered object is then illegally exported after the effective date of the patrimony law, the argument is made that it is stolen property.

“Unlike typical criminal investigations, the New York District Attorney’s primary purpose appears to be to return antiquities to their countries of origin or modern discovery, assuming the office can verify the appropriate country.”

The court papers also note that when such returns are made, the media report the returns as involving “looted antiquities” – evidence of any such looting, if it exists, is rarely made clear.

As ADA chairman Joanna van der Lande wrote to ATG in the wake of the $19 million claim: “It’s time that the media challenged official bodies, from the Manhattan D.A.’s office to UNESCO, the European Commission, Europol and others, and subject them to the same level of scrutiny that they apply to the market rather than just accepting what they put out in statements. Let’s have the same transparency and due diligence when it comes to ‘facts’ that these bodies so readily demand of dealers and auction houses in relation to objects.”

by ADA | Sep 20, 2023 | Views

How do those buying antiquities protect themselves and the public?

Anyone buying items online needs to ensure that what they are paying for is genuine and that the seller has the right to sell them. That’s true for ordinary household goods and consumer wares, and especially true when it comes to the trade in antiquities.

The two trade associations supporting the Antiquities Forum, the UK-based Antiquities Dealers’ Association (ADA) and the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA), have long pioneered policy on this. Having a clear and effective crime-prevention policy is the best way of safeguarding their members and their members’ reputation, as well as boosting confidence in the trade among the public. It is also essential for preventing ancient artefacts being exploited by the unscrupulous.

In doing this, the two essential considerations are Provenance and Due Diligence. But what do they mean?

Provenance is the history of an object, tracing its ownership back as far as possible to ensure that it remains an item that can legitimately be traded. The ADA sets out a detailed summary of the different types of provenance an object can have, what that means and why it is important, on this website.

Due diligence, meanwhile, is the process which trade professionals undertake to ensure that the items they are handling are authentic and can be traded legitimately. It is important to remember that in the event of any legal dispute, the effectiveness of the due diligence undertaken by those responsible will be taken into account.

Effective due diligence is a vital part of protecting traders’ good reputations, which are essential for success in business.

What the associations have to say

The ADA sets out the process of due diligence for its members as follows:

Before offering property for sale, members must be satisfied that they have conducted the level of due diligence required to establish that the property they are handling is authentic and that there are no known legal obstacles to selling and passing title.

The ADA requires members to adhere to the relevant domestic and international laws that govern the markets for archaeological and ancient property and, in many respects, ADA standards go beyond the legal requirements.

If members are not certain as to the laws of a particular jurisdiction, or their application to a specific item, please consult the ADA Council for advice.

Members must act in good faith throughout all transactions.

Members should record each transaction with diligence and keep records for a minimum of 6 years.

Where a member is buying from another dealer or an auction house then the member should record the transaction and note the provenance as provided. Some items will have more detailed provenance than others.

Where a member is buying from a person other than a dealer or an auction house then the member should establish the identity of the vendor. Unless the vendor is well known to the dealer, where an item is worth over £3,000 then member should request photographic identification and if practical take and retain a copy of it. Members should obtain in writing:

- The name and address of the vendor;

- A warranty that the vendor has good title to the objects;

- Confirmation of where, when and how the vendor obtained the objects, as can be provided by the vendor;

- Where the vendor acquired the objects outside the United Kingdom, confirmation that the item has been exported or imported in conformity with local laws and where available evidence of that.

In addition, wherever possible members should arrange payment by a method that leaves an audit.

Lawful Trading

Members undertake to carry out due diligence, as set out under this Code, to ensure, as far as they are able, that objects in which they trade were not stolen from excavations, architectural monuments, public institutions or private property and are lawfully on the market for sale.

Members will make all reasonable enquiries to ascertain earlier ownership history of any object they are considering purchasing, mindful that the illicit removal of archaeological objects from their original context is damaging to our knowledge and understanding of the past.

Members have a duty to record and preserve relevant prior ownership history of an object along with any evidence supplied.

Stolen Art Databases

“It is a condition of membership that all goods acquired at the purchase price of £3,000 or more be checked with an appropriate stolen art database, unless they have already been so checked.’

No system is perfect and many items have very little documented information establishing a detailed history going back decades or longer. This does not necessarily mean that there is anything wrong as there can be a number of valid reasons for this: for instance, paperwork may have been lost or not kept – in the past, such information was not deemed important, as it is today.

As can be seen from the due diligence requirements set out above, however, a higher level of checking is demanded for higher value items.

Market professionals also tend to have effective antennae for picking up ‘red flags’. Remember, just like anyone else, they do not want to hand over ready money for something that may later turn out to be a problem.

Additional things they look out for include items that are significantly under-priced, as this may point to someone handling stolen goods trying to offload them. Another thing to check is how credible the seller is as a source of the material being offered.

The ADA and IADAA have both been proactive in developing due diligence over the years. Indeed, UNESCO’s code of conduct in this field was based on the earlier code published by IADAA.

Both the ADA and IADAA provide further advice on their websites at www.theada.co.uk and www.iadaa.org

Recent Comments