by ADA | Aug 29, 2023 | Uncategorized, Views

Even when an antiquities dealer proves to be the hero of the hour, the media and others try to blame the market instead of those responsible

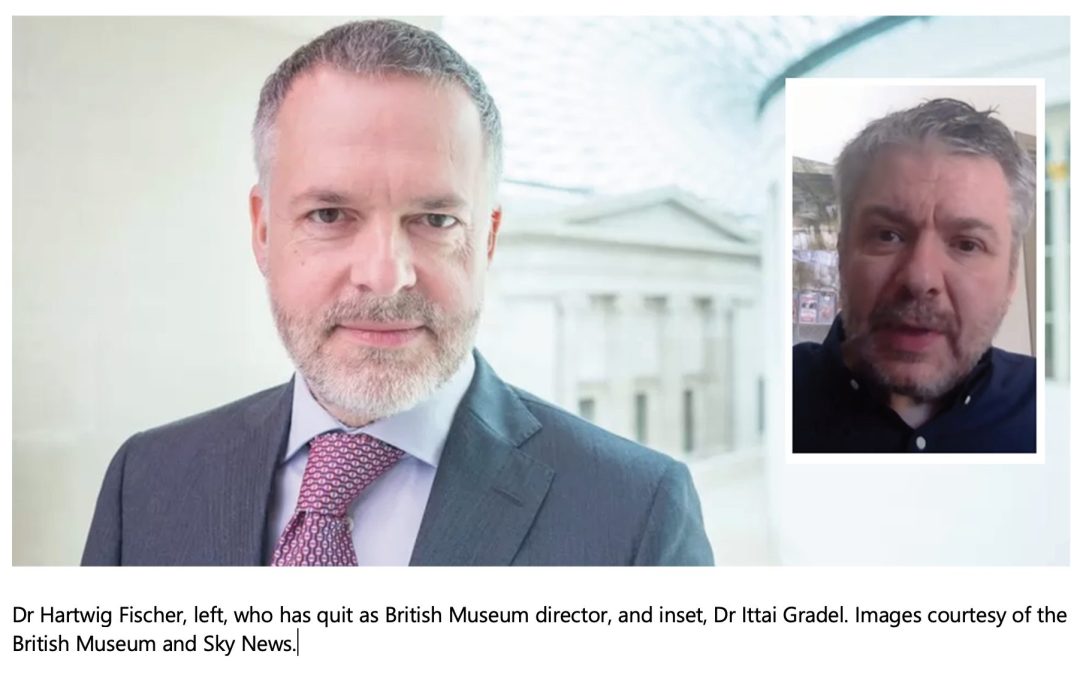

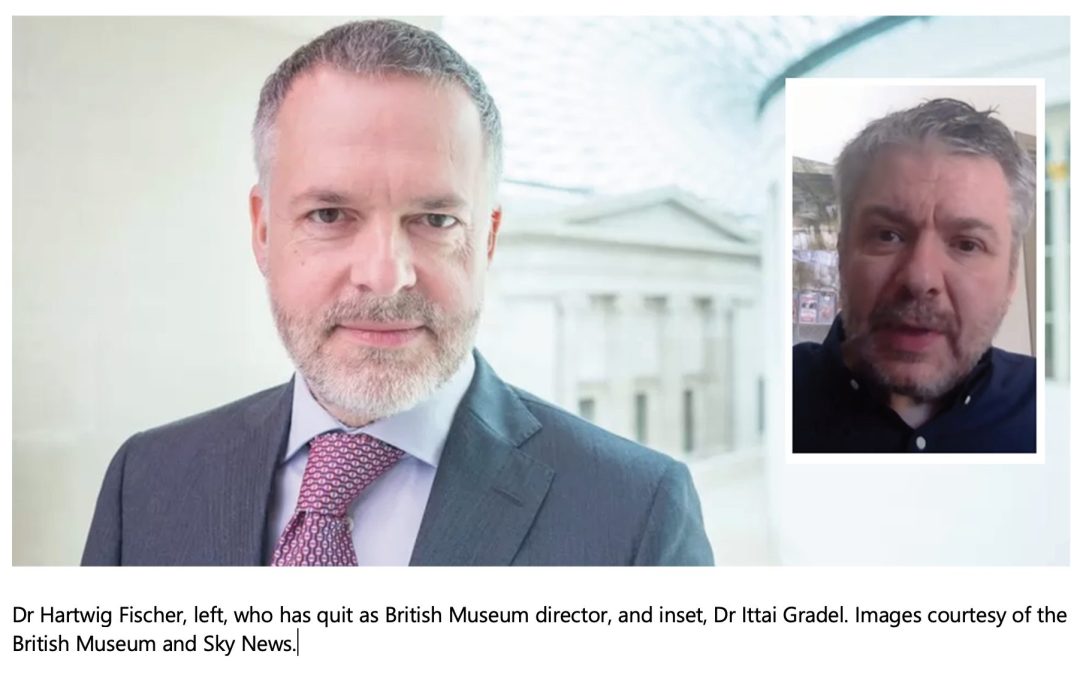

Much of the past ten days has been taken up with the thefts scandal at the British Museum. A senior curator sacked, the director of the museum quitting early, and the deputy director stepping back from duties pending an investigation.

Covered in disgrace, senior executives made their position worse by attempting to divert blame to the man who had blown the whistle in the first place, even though he had spent several years trying to get them to take him seriously.

Why did they think they might get away with it? Perhaps because Dr Ittai Gradel, an academic and collector of antiquities, is also a dealer. And perhaps, too, because history shows us that the media are all too ready to believe the worst of the trade even when confronted by evidence to the contrary.

BM director Dr Hartwig Fischer was quoted as follows: “When allegations were brought to us in 2021, we took them incredibly seriously, and immediately set up an investigation.

“Concerns were only raised about a small number of items, and our investigation concluded that those items were all accounted for.

“We now have reason to believe that the individual who raised concerns had many more items in his possession, and it’s frustrating that that was not revealed to us as it would have aided our investigations.”

Dismissing these claims as “lies”, Dr Gradel accused the director of “shooting the messenger”: “They never even contacted me. I was waiting the whole time for them to ask me to give testimony. Why can’t they just own up to their responsibility?”

Excoriating censure by the Telegraph

Fortunately The Telegraph, which had secured the scoop on the story, had conducted a thorough investigation of the email trail between Dr Gradel and the BM, so it knew who was telling the truth. It went so far as to publish a leader article on August 25 censuring the BM management: “Although the British Museum ostensibly opened an investigation, it reached a swift conclusion that nothing untoward had happened. Now we know that was not the case… the whistleblower gave the British Museum the opportunity to stem the disappearances without publicity. For it to supposedly take no action was a dereliction of duty and has made it harder to argue against demands for the repatriation of important parts of the collection such as the Elgin Marbles.”

Most damningly, the Telegraph concluded: “Why are those accused of ignoring warnings still in post? If they refuse to resign then George Osborne, the UK’s former chief finance minister and now museum’s chairman, should dismiss them for tarnishing the reputation of a great institution.”

While Dr Fischer’s crisis management proved a disaster for him and the museum, as one of the two most senior government ministers in the land during the David Cameron premiership, Mr Osborne is a seasoned politician with a much more authoritative grasp on the playbook of public opinion and reacted accordingly to limit the damage. He revealed that some items had been recovered, calling it “a silver lining to a dark cloud”.

In a BBC interview, Mr Osborne also revealed what he thought had gone wrong in the failure to address Dr Gradel’s concerns promptly: “…was there some potential groupthink in the museum at the time, at the very top of the museum, that just couldn’t believe that an insider was stealing things, couldn’t believe that one of the members of staff were doing this? Yes, that’s very possible.”

IADAA and ADA adviser Ivan Macquisten was quoted in The Times, explaining the importance of the trade’s role in crime prevention, as the media turned its attention to the unwelcome challenges that the possible sale of so many stolen items might pose.

It became clear that many of the missing items had never been properly catalogued or photographed, meaning they will probably never be identified or restored to the British Museum’s collection. Nonetheless, the most strenuous efforts must be made to recover as much as possible.

Trade associations launch media campaign over crisis

Both IADAA and the ADA launched a media campaign on August 25 calling on the British Museum to publish a full list of the missing objects, together with photographs, prominently on its website as a matter of urgency so that the trade and others can help in their safe recovery. Mr Osborne has said that only the police can publish a list on the Interpol website and that the BM is working with the Art Loss Register, adding that simply publishing the list itself might not bring the best response. This was unconvincing. The Art Loss Register is unlikely to focus on less important items among those stolen, and regardless of what other measures the BM is taking, it should also publish the list prominently on its website to ensure the greatest public awareness in the quest for recovery. If that is too much to ask, the least it could do is to provide the correct information to dealers and auction houses for enhanced due diligence.

Despite it being a member of the antiquities trade who devoted four years to uncovering the scandal and reporting it, some commentators have used the scandal to attack the trade.

Foremost of these is anti-trade campaigner Morgan Belzic, doctor in archaeology at the French Archaeological Mission in Libya, who reportedly told classicist Daisy Dunn, also writing for The Telegraph: “The London art market is one of the most involved in antiquities theft and looting… It can move objects very easily and quickly out of the country. It’s one of the least controlled markets in the world. There’s a lot of complacency, a lot of negligence and, of course, some dealers are directly involved with the illegal trade.”

Belzic stuck the knife in further with bogus statistics: “I’d estimate the legal art and antiquities market is only 20 per cent of the total trade,” he said. “It’s impossible to give an accurate number, so little research has been done in the field, but the illegal trade is certainly in the billions [of pounds].”

If it is impossible to give an accurate number, how can he estimate that the legal market is only 20 per cent of the total trade?

He is clearly also unaware of the recently published Cambridge University paper by Dr Neil Brodie and Assistant Professor Donna Yates, The illicit trade in antiquities is not the world’s third largest illicit trade: a critical evaluation of a factoid, or the 2020 RAND report, the latter of which demonstrates convincingly why any illicit trade in antiquities could not be worth billions of dollars – a logical point earlier noted by the ADA’s and IADAA’s own analysis.

Hypocritical approach of trade’s critics

Belzic follows the pattern of many critics of the trade by demanding unquestionable documented provenance for their claims over artefacts, while considering himself free to make wild, inaccurate and damaging claims about the trade without offering any provenance to support what he has to say. He makes a very serious allegation, accusing London dealers of criminal activity. If he has proof of this, why does he not name them? His careless approach is irresponsible.

The additional problem with this is that it is such critics, spreading the bogus claims over an illicit trade worth billions of pounds, who themselves risk encouraging further looting by those who think they are going to make a fortune from such thefts when the reality is otherwise.

One of the more important aspects of this whole sorry saga is the spotlight it has thrown on the politicisation of the museum sector and how it is run. In a letter to The Times on August 25, the former curator of Salisbury Museum, Peter Saunders, agreed with an earlier comment piece decrying the way that museums were losing their way: “…museums have too long felt pressured by funders and politicians to focus on flavour-of-the-month matters such as decolonisation, equality, diversity, restitution and climate change, to the detriment of basic, old-fashioned curatorship. Cataloguing and security are unglamorous activities. Yet might a national scheme to mark all collections with DNA identifiers to deter theft and aid police recovery of stolen artefacts not prove attractive to sponsors? It would surely help prevent the sort of ‘plundering’ suffered by the British Museum.”

The scandal has also led to other issues coming to light. In an August 18 article, Thefts by staff a common problem in UK museums, say experts, The Guardian reported on claims from a former London Museum employee that the sector was :”institutionally corrupt”, with the theft of items being considered “fair game”.

Even after all this, with Dr Gradel doing everyone the greatest of favours by his hard work and determination – and the museum world exposed as having a very serious institutionalised problem – elements of the media exploited the crisis to attack the trade once more.

Article full of unwarranted smears

In an article that didn’t even bother to consult anyone in the trade, on August 28 The Guardian fired a series of unprofessional and unsubstantiated smears against the market, starting with: “Close observers of the antiquities market tend to be a cynical bunch, having witnessed any number of scams, dubious practices and illicit trading.”

In what appeared to approach a defamatory line, it went on to ignore all the reasons Dr Gradel had given to explain why he had kept in contact and continued to buy from the BM thief – building a case, keeping him on the hook etc. Instead it questioned his probity: “After all, the only reason the story about the British Museum has come to light is because a Danish antiques dealer, Ittai Gradel, says he became suspicious about a dealer with whom he continued trading for several years.”

It then added to the insult with the following:

“According to Gradel, he alerted George Osborne, the museum’s chairman, after being “fobbed off” by its managers for two years. Apparently he first had doubts about one seller back in 2016, when he recognised an item he’d seen many years before at the British Museum. When he asked the seller, whom he’d been dealing with since 2014, where he came by his objects, he was told that the man’s grandfather had owned a junk shop in York between the wars.

“That’s the kind of cover story that allows both parties involved to continue with business without having to explore any more awkward questions or pay an expert to establish provenance, even though it is a dealer’s legal responsibility to do just that.

“It took Gradel a further four years before he says he realised that he had been inadvertently handling the seller’s stolen goods. And that’s when, he says, the British Museum started dragging its feet.”

Journalist did not even speak to Gradel or trade as he attacked them

This is an extensive and unfair criticism of the whistleblower by a journalist who has not even had the courtesy to speak to him – even at a time when Dr Gradel was conducting a major round of media interviews. Why not?

The article then questions whether a dealer buying from someone from the British Museum would have a duty to conduct due diligence, as though that did not happen. It is the fact that Dr Gradel did conduct such checks that led to his discovery, a fact that The Guardian ignores.

What it does do is talk extensively to the trade’s arch critic, Dr Christos Tsirogiannis, who says: “It’s a huge red flag,” agrees Tsirogiannis, “but on the other hand, how many dealers of antiquities out there are not dealing with unprovenanced objects? I don’t know anyone.”

As usual, in launching this attack on the trade, Dr Tsirogiannis ignores the reality of provenance surrounding ancient objects: that few, if any, have comprehensive documentation dating back to the point of creation or discovery because of the fact that they are so old and that either such paperwork never existed or has not survived.

If the journalist involved, Andrew Anthony, had dug a little deeper, spoken to someone from the Antiquities Dealers’ Association, or at least bothered to check the ADA website, he would have found all the illuminating answers he needed, from the association’s position on responsible collecting, through its mass of independently verifiable data to its analysis of ethics, due diligence, provenance and provenance research.

by ADA | Aug 9, 2023 | News, Views |

The introduction of the new Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2021 in Western Australia on July 1 has proved such a disaster that it has been scrapped after little more than a month.

Announcing the withdrawal, Premier Roger Cook said: “Put simply the laws went too far, were too prescriptive, too complicated and placed unnecessary burdens on everyday Western Australian property owners.”

As the Brisbane Times concluded: “It’s hard to think of a bigger lawmaking failure in recent political history than the WA government’s impending backflip on its Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act.”

Why is this of interest to the world of antiquities? Because it deals with the same competing priorities that cause friction between commercial and personal interests on the one hand and heritage campaigners on the other, and because it shows what can happen when you tip the balance too far in one direction.

The news that the 2021 Act would be scrapped came after fears that the legislation, which undermined personal property rights for a huge section of business, farming and the public, in favour of the cultural heritage rights of indigenous peoples, might be extended across Australia.

One example of how enforcement of the law had an immediate and stifling impact was the cancellation of civic tree-planting ceremonies after an Aboriginal land corporation demanded $2.5 million to allow them to go ahead.

WA Premier Roger Cook had come under personal attack over the measures, which he refused to delay after complaints that the law was poorly written and its likely impact unclear.

He introduced the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2021 (ACH Act) after Rio Tinto destroyed sacred rock shelters at Juukan Gorge while searching for iron ore in May 2020, despite being warned of their significance earlier. Rio Tinto later apologised, and the CEO and other senior executives later resigned over the matter.

Redefining the meaning of Cultural Heritage

Section 18 of the original 1972 Aboriginal Heritage Act, which held sway until now, provided for land owners to proceed with activities that might be severely damaging to cultural heritage interests if granted permission by the government after a review.

The new act redefined the meaning of Aboriginal cultural heritage so that it was no longer limited to places and objects but also included cultural landscapes and intangible elements, although what they might be was uncertain.

It also replaced Section 18 with far tighter restrictions on property over 1,100 sqm, with permissions to be sought via Local Cultural Aboriginal Heritage Services (LCAHS), bodies that have yet to be fully established.

Effectively the Act gave Aboriginal bodies a direct and greater say – tantamount to a veto – over what landowners could do with their land through the oversight of a new Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Council (ACHC) to whom the LCAHS report.

The type of work covered could be as simple as putting up a new fence or updating irrigation works, as well as more complex projects.

Successful applications by landowners would be issued with an ACH permit, while those of greatest concern winning that approval also had to provide a management plan before going ahead.

Even when they had complied fully with all this at their own expense, landowners risked seeing their plans cast aside if new information arose concerning heritage aspects of the site.

New law “suffocates” private property rights

Those opposed to the early introduction of the law said its statutory guidelines, published at the end of May, were not clear.

Sky News political commentator Caroline Di Russo argued the new law was much worse, saying it “suffocates” private property rights of landowners, and adding that it is “the most disproportionate and overblown response imaginable”.

Red tape and ambiguity would plague farmers and industry as they tried to comply under the threat of prosecution and even jail, Russo said. Even where permission was eventually granted, it was unclear how long the drawn-out process would take.

Despite the extended definition of Aboriginal cultural heritage, Western Australia’s planning chief, Anthony Kannis, who had ultimate responsibility for overseeing the changes, was unable to define what would be covered when asked about this in a question-and-answer session with ABC News, saying “…if there is any doubt whatsoever about the advice you’re getting, there are opportunities to consult with us as a department and raise questions with us”.

One farmer whose family had farmed land in the region for over 50 years had deliberately preserved 1,000 hectares of forest country for decades, only to be told by Mr Kannis that a decision to clear it using fire in keeping with Aboriginal tradition was a possibility if the ACH ruled in its favour. “This is about giving Aboriginal people a say, and that shouldn’t be lost in all this discussion,” he countered.

In what the Financial Review dismissed as “farcical scenes”, at a forum hosted by the Association of Mining and Exploration Companies, “one mining executive asked government officials whether planting a tree near the Swan River in Perth would require a site inspection by traditional owners and the preparation of a heritage management plan.

“The officials replied it would depend on the size of the tree.”

The estimated cost of consulting what Mr Kannis described as “knowledge holders” ranged between AUS$80 and AUS$280 per hour (≠ £42/$55) (≠ £140/$150).

However, as the Financial Review also noted, “Junior exploration companies complained of being charged upwards of $200,000 for heritage surveys in the lead up to the new laws coming into force and said the rollout had been shambolic.”

Penalties for those in breach of the law included fines that started at AUS$20,000 for moving or selling ACH objects. An individual seriously harming ACH could be fined AUS$1m, while a corporation could be fined AUS$10m, with both also risking jail terms.

Concern led to scrapping of fines for initial period

Such was the concern over this amid confusion over how the law would be interpreted that Mr Cook scrapped fines for the first 12 months of enforcement while the legislation bedded down.

The WA government dismissed calls for a review, even after a petition launched by the Pastoralists and Graziers Association demanding a six-month delay raised 27,000 signatures.

Mr Cook ruled out any delay to the new regulations, despite the widespread concern, saying: “The laws are about a simpler, fairer, like-for-like transition of the current laws already in place.”

However, reality soon struck, with the impact on mining interests, as well as farming, seen as devastating. Support for the government plummeted.

Meanwhile, having secured a cultural hegemony via the new law, Aboriginal Heritage groups are now furious at the WA government change of heart.

In all, this was a textbook case in how not to address the valid concerns of indigenous groups as they fight to protect their culture. The WA government under Roger Cook dismissed the equally valid concerns of ordinary people in protecting fundamental human rights relating to property. In turn, this infringement blighted the economy in such a way that much of it risked grinding to a halt in weeks if not days. And that would have driven a deeper wedge between the competing interests of landowners and indigenous groups.

Add to all this the predictable risk of abuse of power by heritage groups handed almost unlimited say in what landowners could do, and the government had prepared the ground for toxic levels of corruption when it came to consultancy fees.

Now Mr Cook is being forced to re-adopt the 1972 law that he had argued was problematic. Having overseen this catastrophic and avoidable policy change, his credibility in seeking to resolve the issue any time soon is in tatters, and he will be doubtless focused now on shoring up support.

His arrogance in dismissing the loud and valid concerns of farmers and others as he declared the new law “simpler, fairer, like-for-like” won’t be forgotten any time soon.

WA disaster an object lesson for law makers

The WA disaster is an object lesson for law makers across the globe when it comes to balancing commercial and private interests with the demands of heritage groups. Effective policy means a nuanced approach that takes both into account, not throwing one side to the wolves in the hope of ingratiating yourself with the other.

Failure to strike this balance despite being obliged to do so by a clear policy directive does not augur well for the European Union’s import licensing regulation (2019/880) for cultural property, due to be enforced from June 2025. The damage to the international art market, including that of the EU itself, as well as the infringement of ordinary people’s rights, is likely to be widespread if that goes ahead – and Brussels has been alerted to this this often, but continues to ignore the warnings.

Too often laws are ushered through with barely a nod at genuine scrutiny of the concerns of all stakeholders. As the Brisbane Times concluded about the WA affair: “Had there been a robust parliamentary debate the practical issues that eventually emerged may have been ironed out before the laws came into effect on July 1.”

The European Commission would do well to look closely at what has just happened in Western Australia.

by ADA | Jul 10, 2023 | Views

As the UK Parliament amends the rules on detectorist and other heritage discoveries, ADA chairman Joanna van der Lande reflects on its role and effectiveness

When Chris Chafin of The House, the Politics Home magazine for the UK parliament, asked to interview ADA chairman Joanna van der Lande about changes to the Treasure Act, it proved an excellent opportunity to reflect on the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

No system is perfect, but the PAS comes closer than any other Joanna knows of balancing the interests of the nation with those of individuals who devote their own time and money to helping us uncover the past in an informative way that protects our heritage.

Just published, Chafin’s article, titled Treasure Island, explains how and why the changes are being made, and what factors must be considered in revising our heritage laws such as this.

Understandably, he could not include the full answers to all of the questions on the trade’s perspective, which he asked Joanna, so here they are for your interest:

Can you briefly give me an idea of how private antiques dealers traditionally interact with the Treasure Act?

Private antique dealers really only interact either as Valuers for the Treasure Valuation Committee or as independent valuers for the finder. There is no reason for dealers to be involved within the process.

I’m sure you’re familiar with the changes which have now gone through to the Act. Do you generally consider them well-considered, or do you feel they fall short in any way?

Generally, my association and colleagues in the trade think the changes have been well considered after a fair period of consultation with all parties concerned. With a certain subjective measure now introduced into the Treasure system, the trade awaits further guidance prior to the changes coming into force in July.

What effect do you anticipate them having?

Very few finds are of the importance covered by the changes, so any impact should be minimal, but it will mean previously significant British finds will not end up at auction. This means museums will have to worry less about raising funds for bidding bid at auction, or about being outbid. It also means that finders and landowners may benefit less from huge auction prices, as significant finds auctioned in recent years have often exceeded pre-auction estimates. I have no doubt the Treasure Valuation Committee and their valuers will understand the implications of fewer comparable objects appearing on the market which are used to help value treasure finds.

There is a great deal of respect for the Treasure system and the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which are extremely well run and been successful in building bridges with all the groups involved.

Much of the discussion around these changes from members of government poses a kind of public/private dichotomy, where things sold at auction “disappear” into private collections. What’s your reaction to those lines of argument?

I think they demonstrate little understanding of what motivates a collector, but they do expose the difficulties collectors face in this age of repatriation and returns, where private ownership of cultural objects is often demonised. Many museums and academics appear to be distancing themselves more and more from the private sector. It is important that for the public benefit we re-kindle museums’ and academics’ increasingly fractured relationships with the trade.

Private collectors and the trade have a wealth of knowledge, gained by many years of experience, as well as personal study, to offer. They have the advantage over museum curators of seeing many more fresh objects as they pass through their hands. This knowledge and experience should be shared.

Pieces rarely disappear completely from public view. While some collectors seek privacy, collections inevitably reappear on the market at some point. Also, there is a long-standing tradition of private collectors publishing their collections, either online or in books, at their own expense. In addition, it is very unusual for dealers not to have their stock listed publicly online or in printed catalogues; the same applies to auction houses.

Privately owned cultural objects have never been so visible and often at considerable risk to collector and trade alike in terms of security and insurance. Added to that are the frequent claims from foreign embassies and campaigners making public demands for the return of cultural objects, even where there is no valid reason for doing so. The media tend to lap these up because they make a good story, but rarely question the validity of these demands.

The situation is different with British finds because there are no foreign claims on them; the trade is very supportive of significant British finds remaining in the United Kingdom and in the public domain.

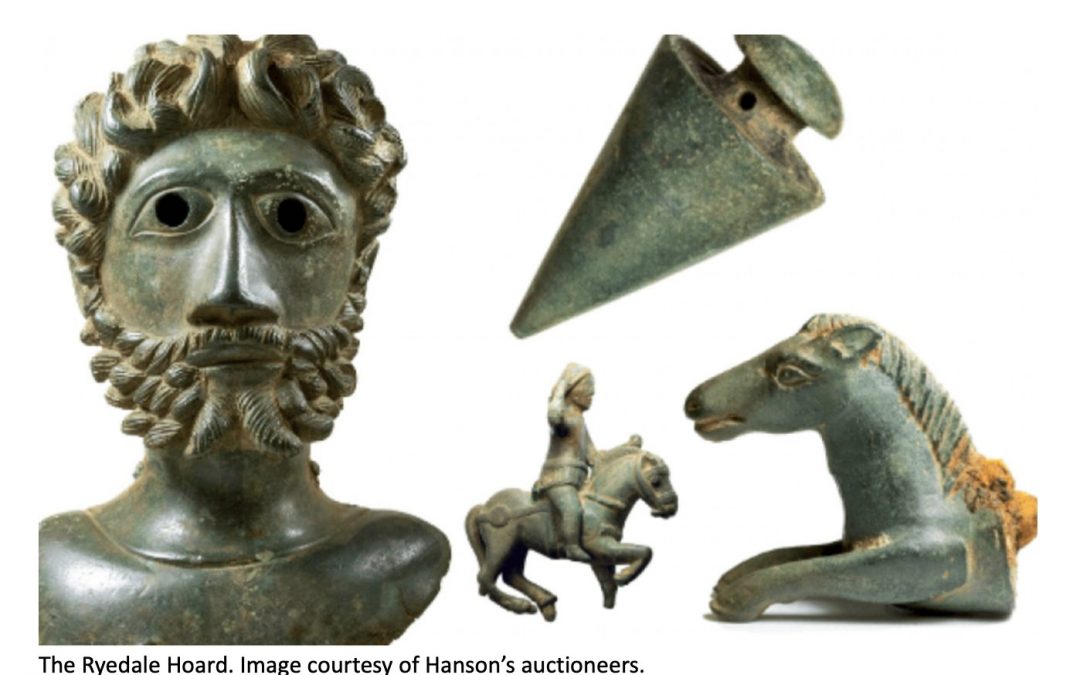

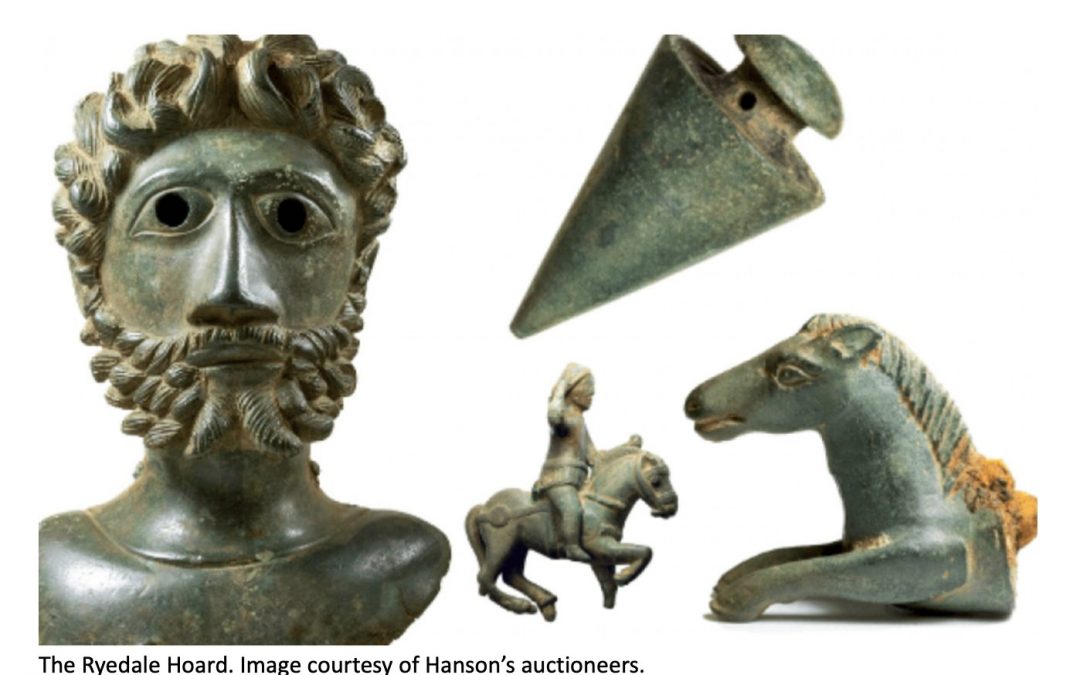

A member of my trade association was the winning bidder of the Ryedale Hoard when it came up for auction in 2021. There was understandable upset that York Museum lost out to higher bidders, but it all came out well in the end. That was because the winning bidder, a dealer, got together with a private numismatics collector and others to negotiate a deal for the hoard to be gifted to York Museum, where it is now on public display. The Crosby Garrett helmet, cited as a catalyst for the amendments to the Treasure Act, might have sold to a private collector, but that collector has loaned it for public display four times already.

One of the benefits of the legislative changes should be to reduce friction between museums, collectors, detectorists and the trade. This is, however, only possible because the system, unique to the UK, is admirably fair and largely respected by all parties – the composition of the Treasure Valuation Committee reflects this. It is a system we can all be proud of, but these are complex relationships that we need to constantly nourish and help evolve – it is easy for misunderstandings to arise.

Are there any other areas of antiques law where you feel changes are needed?

The wider antiques trade (so not just antiquities) has been subject to many legal and regulatory changes in recent years, the two most notable being the Ivory Act and the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive.

The Ivory Act will soon extend beyond the ban in antique elephant ivory. Whatever the benefits to the natural world – and the jury is out over whether a single elephant’s life will have been saved – it will mean the destruction or loss of pieces containing antique ivory that is not of museum quality and will be rendered unsalable. We can see the impact already as objects containing more than the maximum amount of ivory allowed for trade are being dismembered.

I think we need to be very careful of introducing any more laws that could mean antiques are not protected, as this can put even objects in museums at risk in the long term from deaccession and possible destruction. The Ivory Act has also caused a great deal of damage to relationships.

In a world where ‘up-cycling’, recycling and ‘pre-loved’ are ever more popular, we should be giving tax breaks to support the second-hand goods market – be they old or ancient. The antiques business has long been a trail-blazing business for the green economy, and we should all do more to help it flourish.

Understood if this isn’t your area, but I’ve heard that many small museums don’t have the budget or space to showcase even more objects, which is what these changes would ideally lead to. Do you have any insight there?

The number of objects involved is likely to be under 50 each year, so I can’t see it overwhelming museum storerooms, but it’s an interesting point. Supposedly storerooms are accessible for public study, but the reality is that few people know this, and generally not enough staff are available to allow this to happen. The British Museum and the V&A have less than 1% of their holdings on public display. It would be interesting to conduct a survey of other museums, both in the UK and overseas, to establish what percentage of their holdings are actually on public (or online) display. For museums to fulfil their public benefit remit, they should focus on digitally recording objects for online study.

Any other general comments you’d like to make here?

Although it is an EU law, the new import licensing regulation due to come into force in June 2025 is likely to prove disastrous for art markets across the world, including the three largest, in the US, UK and China. However, the EU art market is likely to suffer the most. The measures are unrealistic, oppressive, unjustified and will prove very costly. They also risk damaging customs operations across the EU.

The EU will essentially close its borders and prevent its private citizens from buying a wide range of cultural objects because the paperwork and costs required will make it impossible. The UK and European trade have been working hard to communicate the dangers posed by this regulation since it began working its way through the European Parliament prior to Brexit, and we continue to do so, collaborating with our European trade partners. However, this is a battle none of us can fight alone.

by ADA | May 22, 2023 | Views |

Europol has admitted not having any reliable statistics to support its headline claim over stolen objects in Operation Pandora VII, aimed at tackling cultural property trafficking.

Many media outlets have covered the results of the latest transnational operation co-ordinated by Interpol and Europol with a view to tackling trafficking in cultural property.

Pandora VII, led by the Guardia Civil in Spain, took place over 11 days in September 2022 with two cyber weeks in May and October.

The Europol media release itself stated that the operation led to the arrest of 60 people and the recovery of 11,049 stolen objects across 14 countries.

As the ADA knows well, there is a great deal of difference between seizing items and showing that they are stolen, just as arrests do not equate with convictions.

These operations, along with others named Athena and Odysseus, have been running for almost a decade, and to our knowledge, the authorities have never published either conviction rates or figures confirming how many seizures later proved justified. The ADA and fellow trade association IADAA have sought this information from Europol more than once, but Europol has replied each time that it does not have it, which makes its official release claim this time that 11,049 seized items were stolen all the more surprising.

The twin priorities in carrying out these operations have always been to clamp down on money laundering and terrorism financing, but while there may have been limited evidence of the former across the years, we have heard of no evidence at all of the latter.

Once again we contacted Europol asking the following: a) How many arrests have led to successful convictions? b) How many seizures proved to be valid + how many had to be returned to their owners? c) How many seizures were shown to be linked to money laundering? d) How many seizures proved to be linked to terrorism financing?

As others have also argued, without these accurate clear-up figures, the data serves no purpose beyond propaganda.

Europol’s media office ADMITS IT HAS NO ACCESS TO VITAL DATA

Europol’s media office replied on May 10 as follows: “Unfortunately, we won’t be able to help as we do not have these figures. Europol is not a statistical organisation – Europol’s priority is to support cross-border investigations and the information available is solely based on investigations supported by Europol.”

Confirmation, then, yet again that Europol has no statistics to support the claims it makes, with the further emphasis that Europol is “not a statistical organisation”. If so, what is it doing making statistical claims it admits it cannot support in the introduction to its media release, claims that history tells us will influence policy at a national and international level, as with the introduction to this recent important European Commission document?

Interpol, which has also denied having any reliable statistical information in this field, compounded the error.

Arguably more shameful is the number of media outlets that have reported the unsupported claims Europol has put out in this release without checking them. Newspapers, art market websites and others – all of them experts in their own fields and trained to check their sources – have singly failed to do so in this case.

They include Yahoo News, Artnet News, Euronews, and Reuters, among others.

It also includes outlets whose credibility entirely relies on accurate data, such as the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, and Border Security Report (the Journal of border security and transnational crime).

This is not the first time this has happened; these operations have been going on for a decade and the ADA and IADAA have highlighted the failure of intelligence on numerous occasions. As we showed in this instance, a single email request revealed the truth. So why can’t the experienced journalists working on this story make such a simple check as this to ensure that their reporting is accurate?

One of the worst offenders was Ursula Scheer, a journalist for Frankfurter Allgemeine, who not only swallowed everything she was told without checking, but added even more bogus data to the story unchecked: “According to estimates by the FBI and UNESCO, the annual turnover of the global black market for art and antiques is ten billion dollars, which puts the black market right behind the illegal drug and arms trade.” She also stated: “Selling art and antiques helps mafia activities finance terrorism and war.”

Those who want to know where the bogus data ends and the accurate data begins can check on our Facts & Figures page, which includes independently verifiable data through quoted sources and direct weblink.

by ADA | Apr 28, 2023 | Views |

In February 2019, the ADA took part in a BBC radio programme entitled Zombie Statistics. It investigated the problem of fake news and misuse of data to promote propaganda, notably against the international art market.

Journalist Ed Butler took UNESCO to task for its manipulation of statistics to suit its policies, while the celebrated statistics guru Dr Tim Harford explained why confirmation bias – the disinclination to check the validity of information that supports your case – feeds into the misuse of data and fake news.

“If you think right is on your side, then you are not going to be too careful checking the claims that fit nicely in your world view,” he concluded.

Harford went on to explain how the publishing of false data by a respected institution or official body gets repeated “ad nauseam” by others and the media until it becomes the truth.

“What’s alarming is that this is affecting policy,” he warned, as instead of creating policy from reliable evidence, you get “policy affected evidence”.

This problem is rampant when it comes to the art market, particularly with antiquities.

The ADA and IADAA have conducted extensive research into this phenomenon and have long exercised a policy of insisting on providing clear primary sources for data, complete with a weblink, where possible, as well as advising anyone who looks at the data to check the sources to satisfy themselves that they are accurate.

This is the only way to reassure an audience that what you are telling them is true. Never ask them to take your word for it.

Taking all of this into account, it is worth reflecting on how a current example of the misuse of data is being used to influence policy makers.

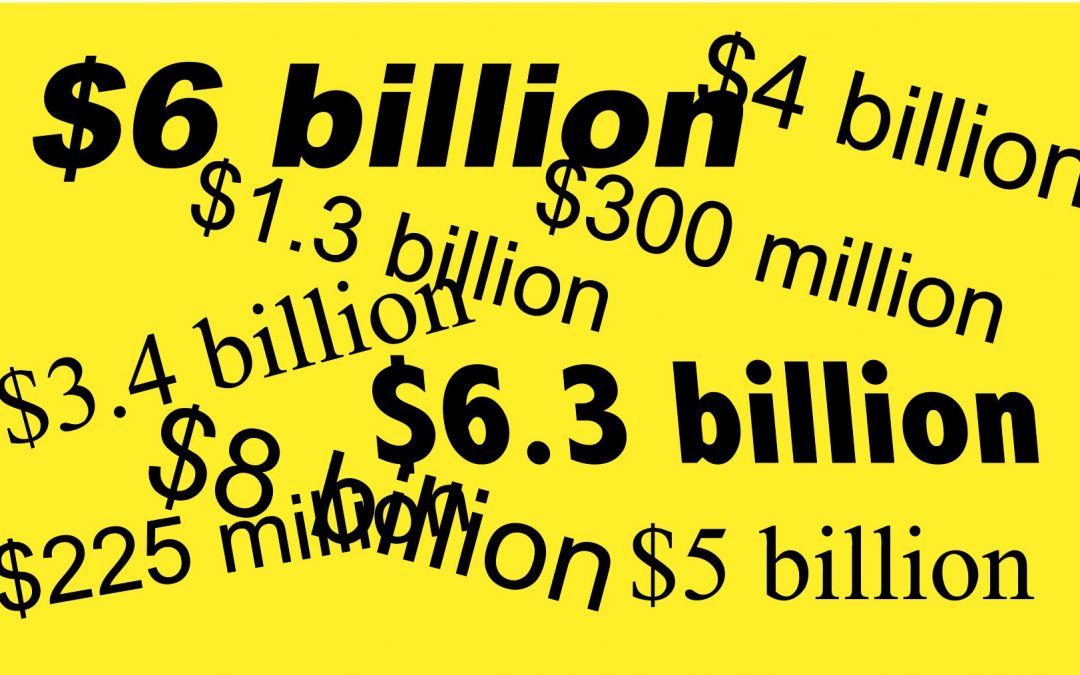

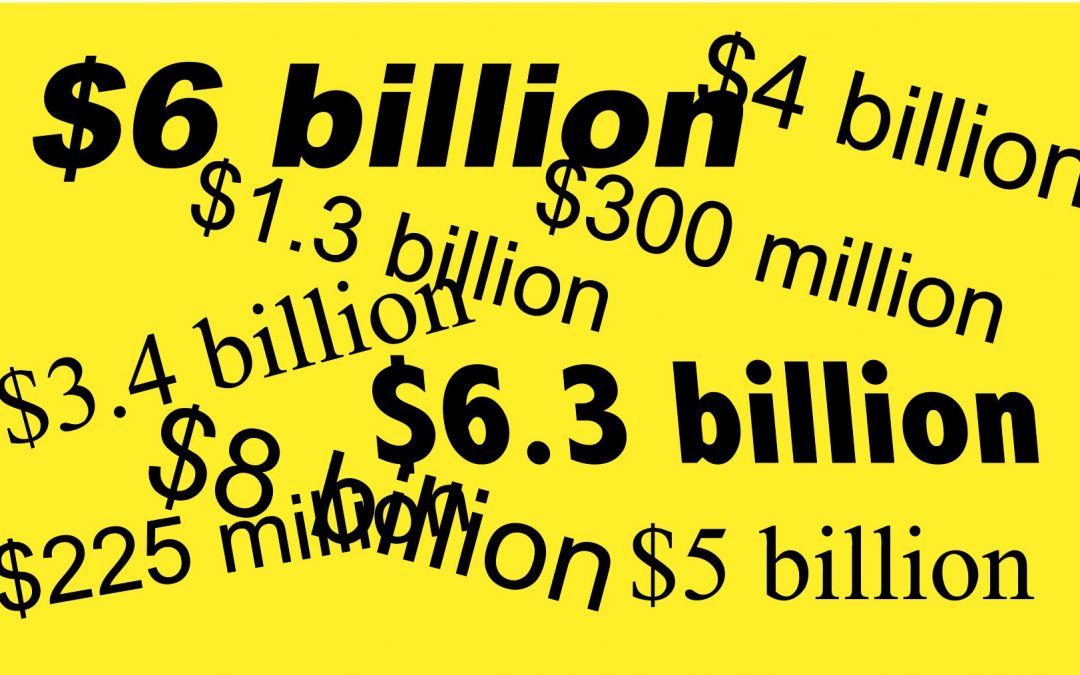

In 2011, the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) published a report entitled Estimating Illicit Financial Flows Resulting from Drug Trafficking and Other Transnational Organized Crimes. On page 36 it gave a value range of $3.4 billion to $6.3 billion* as the GFI estimates of the global proceeds of crime for art and cultural property, stating this estimate was based on information from Interpol and the International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council of the UN Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme.

Apart from the broad range of these values and the fact that they are estimates, at least one of the quoted sources, Interpol, has declared that it has never had any figures – nor is ever likely to obtain any – that could allow it to make such a judgment on the level of art crime. Nor do these figures relate to trafficking, but to all art and cultural property related crime. That’s an awful lot of ifs and buts.

$6 billion to $8 billion

The UNODC report states that its Interpol and UN-related figures come from the February 2011 Global Financial Integrity (GFI) report by Jeremy Hakin, Transnational crime in the Developing World, and World Bank indicators (for current GDP). As can be seen from page 47 of that report, it actually quotes three sets of figures, $300 million to $6 billion, $4 billion to $5 billion and $6 billion to $8 billion. It gives, as its source for the first, page 221 of Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World, by Roger Atwood from 2004. For the second it gives the September 19, 1999 article from The Atlanta Journal Constitution by Mike Toner, The Past in Peril; Buying, Selling, Stealing History. For the third, it gives page 52 of the 2010 report International Report on Crime Prevention and Community Safety: Trends and Perspectives, from the International Centre for the Prevention of Crime, by Idriss, Manar, Manon Jendly, Jacqui Karn, and Massimiliano Mulone.

Crucially, Hakin then states: “This report creates a range by taking the average of the low estimates and the average of the high estimates reported above. The result is an annual value of $3.4 to $6.3 billion.”*

Checking the sources of these sources we come up with the following:

– $300 million to $6 billion: Currently unavailable

– $4 billion to $5 billion: Currently unavailable

– $6 billion to $8 billion: International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council of the United Nations Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme. ISPAC (2009). Organized crime in Art and Antiquities. Selected Papers from the international conference held at Courtmayeur, Italy 12-14th December 2008. Milan: ISPAC.

While the ADA and IADAA intend to research these sources further, it is worth pointing out that they date back, at least, to 2004, 1999 and 2008, and possibly further, so, like the UNODC report itself, hardly relevant for 2023.

While the figures above refer to the 2011 GFI report, page 35 of the same GFI report from 2017 (six years later) puts the estimated value of “the global revenue generated from the illicit trade in cultural property” at “approximately US$1.2 billion to $1.6 billion”. It extrapolates this from the 2008 ISPAC global art crime estimate of $6 billion to $8 billion (see above), based on the assumption that 80% of such crime is fraud-based. In turn, it takes this estimate from two sources: John Powers’ February 2016 article for the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, Fakes, Forgeries and Dirty Deals: Global Fight against Amorphous Art Fraud, and Kris Hollington’s July 22, 2014 Newsweek article, After Drugs and Guns, Art Theft Is the Biggest Criminal Enterprise in the World, a claim now known to be wrong and without foundation.

Powers’ article is no longer available via the web, but Hollington attributes the $6 billion to $8 billion figure to the FBI, without giving a specific source, but would seem to be ISPAC, as shown above.

However, In 2013, the FBI art crime unit estimated all art crime globally concerning everything from Contemporary art to stamps, at around $4 billion to $6 billion. That included crimes such as domestic burglary (the largest single contributor to the figures), vandalism, fraud and so on.

A failure to check Hansard

Another UNODC report, from 2016, repeats two claims:

• The Museums Association has estimated that profits from the illicit antiquities trade range from $225 million and $3 billion per year.

AND

• The organized Crime Group of the United Kingdom Metropolitan Police and INTERPOL has calculated that profits from the illicit antiquities trade amounted to between $300 million and $6 billion per year.

The UNODC gave as its source for the claims the UK House of Commons Culture Select Committee hearings in Cultural property: Return and Illicit Trade, seventh report, volumes 1, 2 and 3, in the year 2000.

What the UNODC clearly did not do was to check that House of Commons source, still available today in Hansard, the official parliamentary record. If it had, it would have found that neither claim stood up.

In the case of the Museums Association, Hansard (Chapter II The problem of illicit trade, The nature and scale of illicit trade paragraph 9) reports:

“The scale of the illicit trade taken is said to be very considerable. According to the Museums Association, ‘as an underground, secretive activity, it is impossible to attach a firm financial value to the illicit trade in cultural material. Estimates of its worldwide extent vary from £150 million up to £2 billion per year.”

The Museums Association talks about “cultural material”, i.e. all art and antiques, not antiquities, gives a range of figures from £150 million to £2 billion a year and attributes it to Geraldine Norman’s Independent article, Sale of the Centuries, from November 24, 1990, which shows no such figures, leading to the conclusion that they have actually taken them from page 23 of the Brodie, Doole and Watson report Stealing History, 2000, which wrongly attributes the figure to Norman. Again, the Museums Association appears not to have checked its primary source.

With regard to the Met Police calculation, Hansard reports the following:

“(Detective Chief Superintendent Coles of the Met Police) I anticipated a question along these lines before I came here. I conducted some research, going back over 10 years, to try and find out where figures that have been bandied around about this subject emanated from. One of the figures is $3 billion. I have found reports going back 10 years where there is an estimate as high as $6 billion. At the other extreme of the scale the suggestion is that it could be as low as $300 million. To try and put some definitive figure upon this scale, my colleague, Miss Stevenson, has conducted some research in the last few days, and it might be better if she explained her research to you.”

“(Detective Constable Stevenson) I think what we have to actually state from the start is that the cases are really anecdotal. There are no statistics kept. We have to bear in mind that the whole trade, whether illicit or legal, actually encompasses jewellery, works of art and antiquities, and as there is no actual Home Office information that is kept we have had to turn to the insurance companies and the insurance industry to get the figures we have.

“A loss adjuster I spoke to estimated that this trade is costing the public between £300-£500 million per year in the United Kingdom alone. I can break that down to where he got those figures from. The Association of British Insurers on average record losses by theft in both domestic and commercial as being somewhere in the region of about £600 million per year. Out of that figure they assume that roughly half relates to domestic theft. So, leaving aside your office break-ins or something like that and computer thefts, they would say that approximately £300 million goes on domestic burglaries, and out of the domestic thefts, roughly, in the settlement, two thirds of the items in that category are jewellery, silver, collectibles and fine art. That accounts for the first £200 million of insured losses.

“Secondly, they state that Lloyds is excluded from the total and, of course, the majority of very high value fine art and antiques are insured through Lloyds. We do know that worldwide Lloyds pay out in the region of about £100 million into the fine art and jewellery category. So, it is possible to estimate that between 40 and 50 per cent of that is attributable to the United Kingdom. That takes the figure to roughly £250 million. Then they looked at the area of uninsured loss, which is extremely difficult to estimate. This would include properties such as National Trust properties, English Heritage and churches, but they reckon that is somewhere in the region of £75 million per annum. Then there are those losses which go entirely unreported, which, of course, you can only guess at, but they arrive somewhere in the region of £300, £400 or £500 million per year.”

As this evidence shows, the $300 million to $6 billion figure is no more than hearsay, which is immediately corrected by the better informed officer, who retorts that no such information or statistics are available. Instead, she reports figures estimated by insurance companies based on losses that are chiefly the result of domestic burglaries – nothing to do with the art market at all, let alone antiquities or trafficking.

As the 2016 report and our research lead us to believe, the UK House of Commons investigation from 2000 is a highly credible candidate as the source of the $6 billion figure later used by the FBI and others.

Remember, it was dismissed hearsay with sources stretching as far back as 1990.

Dubious data from decades ago used to push 2023 report

Now move forward to 2023 and the Financial Action Task Force report, entitled Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in the Art and Antiquities Market, and the $6.3 billion figure arises once again in paragraph 3 of the Introduction on page 5. The FATF burnishes that figure by stating that it is a UNODC estimate, which its own source (the 2011 report) shows is not true. In reality, it is a figure quoted by the UNODC from other uncertain and much older sources, as shown above.

So, a report by the FATF published in February 2023, aimed at influencing current international policy, quotes a highly dubious (at best) 12-year-old estimate based on much earlier estimates as the key statistic relating to global art crime to make its point.

Add to all of this the poorly funded and trained media’s failure to check sources as it takes officialdom at its word – and social media’s tendency to share their stories – and you have all the ingredients for the perfect global viral disinformation campaign.

It would be interesting to hear what Ed Butler and @timharford have to say about all this.

Remember, this is just one example of how unreliable claims and data have been reworked through multiple sources over the decades. As the Bogus Information about the Art Market document published by international trade federation CINOA shows, many other examples now blight official reports issued by authorities on a global scale.

by ADA | Mar 2, 2023 | News, Views

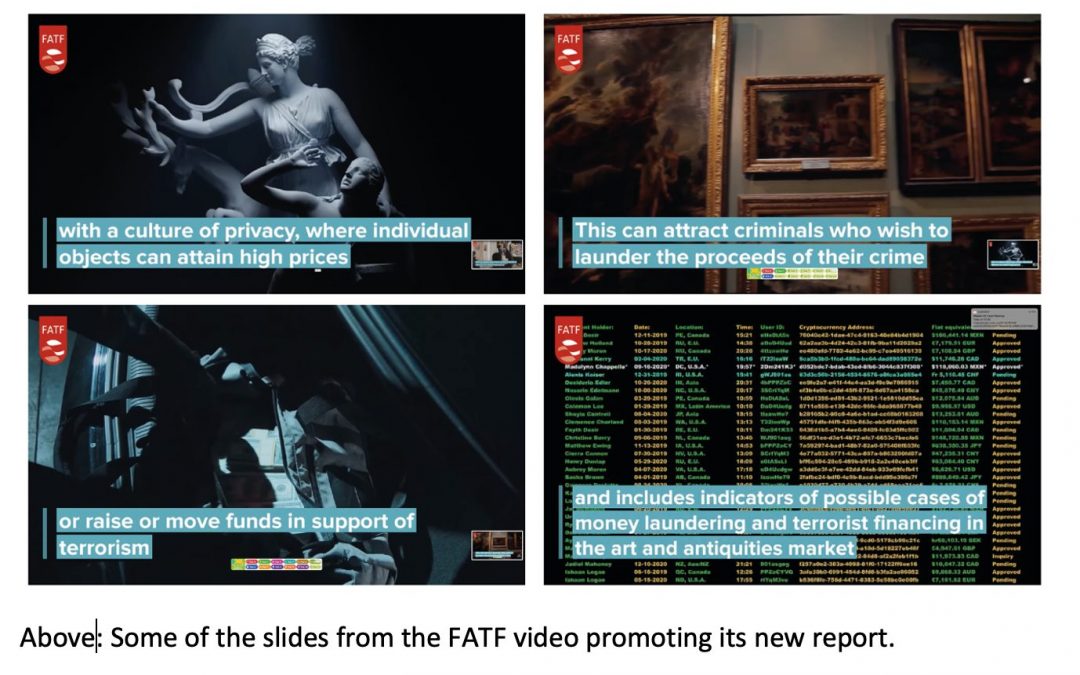

Just released, the Financial Action Task Force’s new report, Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in the Art and Antiquities Market, takes a highly irresponsible approach.

The FATF is an independent global body investigating crime whose reports should prove key to policy making. Not this one, however.

Arguably the most salient conclusion it comes to is as follows: “The markets for art, antiquities and other cultural objects are diverse in size, business models and geographic reach. Most are relatively small, and the vast majority of participants have no connection to illicit activity.”

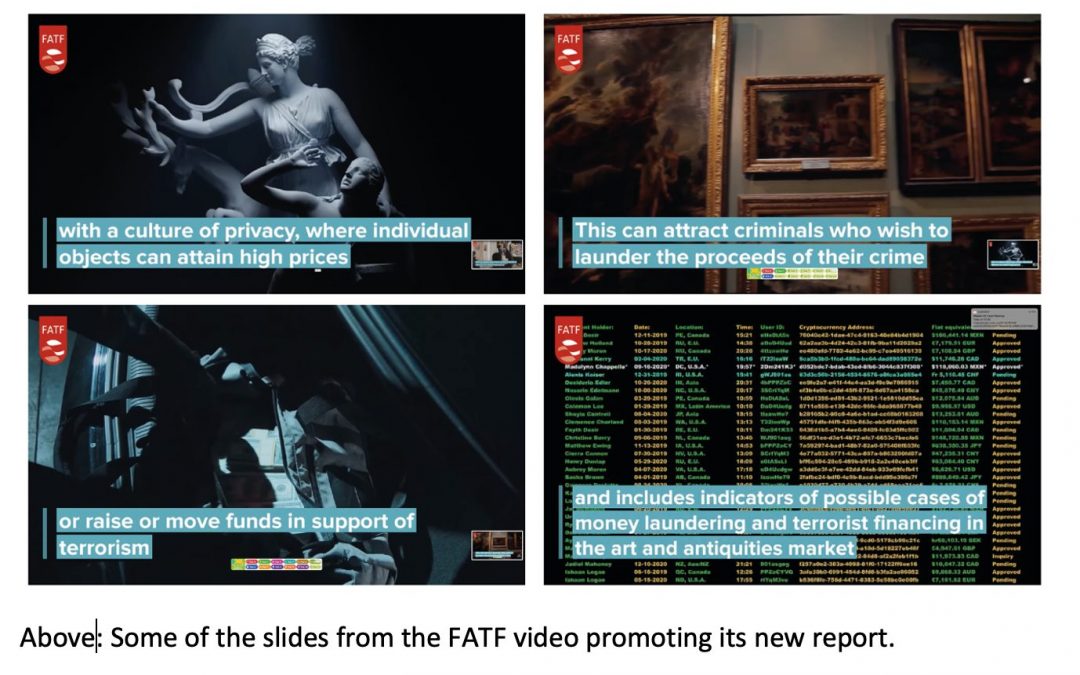

However, this is buried deep in the text, while the FATF has focused on launching the report with a headline grabbing video that gives the clear impression that the art market is awash with criminals committing offences linked to money laundering and terrorism financing.

Needless to say, anti-market forces have leapt on this to condemn the trade and demand further legal restraints, while ignoring the lack of substance in the report or the fact that rigorous anti-money laundering laws already apply in the UK, for instance.

As with so many other reports of this ilk, fact checking has been a casualty. The most important initial independent statistic the report quotes as it launches into its arguments is wrong. In paragraph 3 of the Introduction Background on page 5, it notes that the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) “has estimated that in 2011, as much as USD 6.3 billion in illicit proceeds could have been laundered through or associated with the trade in cultural objects”. In fact, the figure, which was sourced from House of Commons Select Committee evidence in 2000 – now almost a quarter of a century ago – does nothing of the sort as CINOA’s Bogus Statistics report proves. FATF has simply taken UNODC’s word for it, thereby adding to the dissemination of fake news. This being the case, how reliable is the rest of the report?

The FATF’s work is important, so it is a shame that it, too, appears to have fallen into the trap of putting publicity before purpose in drawing attention to itself to justify its existence.

Further analysis of the report will follow.

Recent Comments